The Palestine question is one of the most divisive international issues of our time, in part because there are no serious conflicts among the major world powers, but mainly due to the cultural significance of the people and land in question. Issues of race, religion, and security take the forefront of a problem that also has economic and cultural dimensions. Since it is difficult to find an observer who does not at least tacitly take sides, discussions of the Palestinian question almost invariably omit facts unfavorable to one side’s point of view, making it nearly impossible to obtain an accurate historical perspective. I hope to give a relatively succinct yet thorough description of the relevant facts and issues of the Palestine question, and dispel some common misperceptions in the process.

The first misperception is that Arabs and Jews have intractable racial and religious differences that generate inevitable conflict, and so have been fighting over Palestine for centuries. This is patently untrue, being contradicted by centuries of historical reality. Arab Muslims have occupied Palestine since the seventh century, and for 1200 years they had no major conflicts with the indigenous Jews. During the century of the Crusader states, when Christian lords commanded Arab Muslim armies to ward off the Turks, the only religious riots were between Jewish sects. Jews were respected by Muslims as dhimmi who were not to be persecuted, yet were to live separately from Muslims. This suited the Jews well, as their rigid observance of the Torah required a fair degree of isolation from foreigners, even though they could trade and do business with them. Rabbis did not believe the Jews had a mandate to try to expel the Arabs or establish a Jewish state. They accepted their state of “exile” as a divine judgment, to be ended only when the Messiah comes. Jews and Muslims thus lived peaceably and without threatening aggression all the way into the modern era.

This pre-modern pluralist system served well until the nineteenth century, when liberal ideas of secular nationalism and religious tolerance began to hold sway in Europe and America, and germinated in the Middle East as well, particularly in Egypt and Turkey. No longer was it acceptable to keep ethnic and religious minorities in ghettos. Creating a broader sense of nationalism empowered minorities, yet at the same time it would mean giving up some of their autonomy. In the case of the Jews, the question took on a religious dimension: how could one assimilate in a secular republic while still observing the Hebrew religion, which contains its own public laws?

Secular thinkers of the nineteenth century, both Jewish and non-Jewish, tended to view “the Jewish question” in nationalistic terms. The Jews scattered throughout the world constituted a nation; thus their loyalties were always divided between the Jewish nation and their “host” nation. This dual nationalism could be viewed positively or negatively. Anti-Semites (so named because they opposed the Jews on racial or nationalist grounds, rather than religious grounds) viewed the Jew as a parasite or potential traitor to his host country who ought to be expelled or forced to assimilate. Others were more optimistic about the Jew’s ability to harmonize his twin loyalties, and in this spirit some liberals established Reform synagogues. Still others, accepting the premise that the Jews constituted a nation that ought to be the first loyalty of each member, concluded that the Jews ought to have their own nation. This is Zionism, and it is nothing other than the Jewish version of the nineteenth century nationalism that pervaded all of Europe.

Before the nineteenth century, the words “nation” and “race” were used interchangeably, both meaning people of a common ancestry or birth (natus), or in modern parlance, of common ethnicity. In the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, modern states began to expand and consolidate feudal territories, imposing common legal norms and, significantly, an official language. The expansion of modern states was really limited to language groups, but at the time the project was conceived as bringing together all people of a given “race” or “nation” under one state, so they could live naturally as one society.

Thus all the French were to be brought under one state after the Revolution. Burgundy and Navarre were annexed; Avignon was seized from the papacy, and the French Low Countries were invaded, all in the hopes of creating a single Gallic state. A similar notion of nationality motivated the unification of Italy and later attempts to unify Germany. “Nationalism” became the idea that each “nation” ought to have its own state, by natural right. As nationalist projects came to fruition, the terms “nation” and “state” became almost interchangeable, as in modern usage. The term “race” alone retained its original ethnological meaning, while “nation” or “nationality” became increasingly conceived as political identifications.

It is in this intellectual climate that nascent Zionism drew its strength. Being a Jew was not just a fact of biology or religion, but a political identification with a yet-to-be-realized Jewish nation-state. It is no small irony that Zionists shared the assumption of Anti-Semites that a Jew was necessarily more loyal to other Jews than to his “host” country. The Zionists, of course, viewed this in a positive light, motivating the creation of a good Jewish society that most, if not all, Jews would naturally want to join. The French had their France, and the English had their England, so why should the Jews not have their Judea? In the wake of anti-Jewish violence in Europe, Theodore Herzl’s The Jewish State (1896) widened the appeal of Zionism, at the same time propelling Herzl to the leadership of the First Zionist Congress in Basel the following year. Herzl is often regarded as the founder of Zionism, but there were many influential Zionists before him, and there continued to be Zionist factions who held disparate views.

As a moral and intellectual program, Zionism seemed innocent enough. However, those who took Jewish nationalism seriously enough to propose the question of an actual geographical location for this Jewish state encountered some obvious difficulties. Early Zionist proposals suggested a Jewish state in some remote, sparsely populated location, such as Uganda, Madagascar, the Sinai peninsula, or Argentina’s southern Patagonia region. Aside from being fairly inhospitable locales for those accustomed to a temperate climate, these projects could never go past the planning stage because they never had the cooperation of the nations expected to cede territory. The best hope was for a colonial power such as England or France to give up some of her colonial territory, as in the Uganda and Madagascar plans. It is noteworthy that Palestine was not seriously considered, as the Zionist leadership (as constituted in Jewish international organizations and congresses) was predominantly secular in outlook, so the “Holy Land” held no special calling for them. The majority of Jews, of course, were religious to some extent, so those who were sold on the Zionist ideal would naturally prefer that the Jewish state be in Palestine. As this was part of the Ottoman Empire until World War I, a Palestinian home for the Jewish state was out of the question.

By 1917, the outcome of World War I was already apparent, so the British, French, Italians, and Russians constructed a web of conflicting secret agreements and false promises dividing the soon-to-be-conquered territories and spoils of war. In particular, it was evident that the decrepit Ottoman Empire would finally be dismantled, so the territory of Palestine would be administered by the victorious Europeans.

In order to solidify support for the war among Jewish elites, the British Foreign Secretary Alfred James Balfour wrote a letter (2 November 1917) to Lord Rothschild assuring him:

His Majesty’s Government view with favor the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people, and will use their best endeavors to facilitate the achievement of this object, it being clearly understood that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine, or the rights and political status enjoyed by Jews in any other country.

This letter became public a week later, and Britain became the first world power to support the project of a Jewish nation-state. Notably, the Balfour Declaration specified that this “national home” would be in Palestine. Religious Jewish organizations in Britain protested the Zionist plans, for fear it would create trouble for Jews in Europe, who might be expelled to Palestine. They were ignored, for Balfour’s assurance was aimed to appease the Zionist elites, not the ordinary Jew. Although the Balfour Declaration appears to express full support for the Zionist program, it includes the caveat that “the civil and religious rights” of the Arabs in Palestine must be respected.

After the war, the Americans learned of the secret agreements made by the British, including a letter dated 24 October 1915 from Sir Henry McMahon, the British High Commissioner in Egypt with Husayn, father of the first modern kings of Jordan and Syria. In exchange for Arab support in the form of a revolt against the Ottomans, Husayn was promised Arab autonomy over the Palestine, Lebanon, Syria, Iraq and the Arabian peninsula, excluding Aden and territories that were not entirely Arab. These exceptions were:

The districts of Mersin and Alexandretta, and portions of Syria lying to the west of the districts of Damascus, Homs, Hama, and Aleppo.

Basically, only regions with substantial Christian minorities or majorities were excluded. Palestine was not one of these exceptions. Like the Balfour Declaration, the Husayn-McMahon correspondence was a promise by the government, but not a legally binding agreement. The assurances made to Arabs and Jews were among many contradictory promises that Britain and her allies dealt in order to shore up support for the war. The Americans did not recognize any of these agreements and argued for an application of the then novel legal principle of self-determination of sovereignty.

The definitive mandate system approved by the League of Nations made Palestine a British mandate, effective in 1923. This partially modified the Sykes-Picot agreement (1916) between Britain and France, which had required Palestine (then including present-day Jordan) to be an international mandate run by England, France, and Russia. Under the new system, Palestine (now excluding modern Jordan) would be an exclusively British mandate, freeing Britain to fulfill the promise of the Balfour Declaration. The British mandate, approved by the League of Nations, promised to “secure establishment of a Jewish national home.” The United States Senate also supported this endeavor. A Jewish national home did not yet mean the desire for a politically independent state, even to some Zionists. The goal of political autonomy had to be preceded by establishing a viable Jewish community in Palestine.

As recently as 1880, there were fewer than 25,000 Jews living in Palestine. Most of these lived in Jerusalem, where they constituted half the population. Even this modest amount was largely the product of immigration after 1840, consisting of Jews who made pilgrimages to Jerusalem for religious reasons, often remaining there until death. Baron Rothschild financed Zionist settlers, who numbered only 10,000 by 1891. Socialist Zionists oversaw the immigration of 40,000 Russian Jews into Palestine after the failed revolution of 1905. Unlike previous settlers, these socialists only relied on Jewish labor, encouraged the widespread use of Hebrew, and formed a self-defense organization. From these socialist Zionists would emerge the future leaders of the Israeli state, including David Ben-Gurion.

In this early period of immigration, there was local resistance to Jewish purchase of land and the eviction of Arab tenants, but to no avail, as these transactions were sanctioned by the Ottoman government, since the land reform of 1867 allowed foreigners to own land in exchange for taxes.

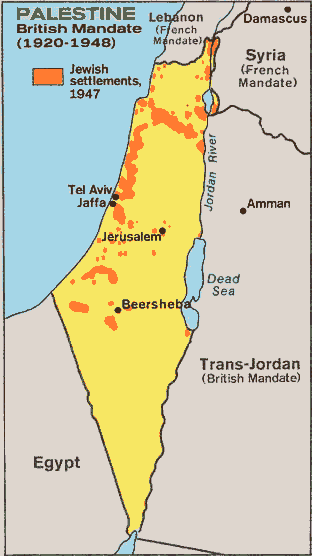

By 1914, the population of Palestine was about 650,000. 80,000–85,000 (12%) were Jews, most of whom immigrated after 1900. Only 12,000 lived on the land, and their combined holdings was an area much smaller than the present Gaza Strip, though their productivity was proportionally much higher. Even after the first two waves of immigration, the overwhelming majority remained Palestinian Arabs, numbering 555,000–585,000, while another 25,000–40,000 were Arabs (and other nationalities) who immigrated after 1840. This demographic picture had changed little by 1922, when the census counted 84,000 Jews, 11% of the total population.

It is only during the British mandate period that a substantial Jewish population began to be established in Palestine. Legal immigration increased the Palestinian Jewish population to 175,000 (17%) in 1931, while Muslims numbered 760,000 (73.5%). In 1945, an Anglo-American survey estimated the Muslim population at 1,077,000 (58%), while Jews numbered 608,000 (33%). Thus during the mandate period, the Jewish population increased by more than 500,000, tripling their percentage of the overall population. During the same period (1922-1945), the Muslim population also increased by 500,000. There were 45,000 legal Arab immigrants into Palestine during this period, plus an estimated 50,000–100,000 illegal Arab immigrants. Meanwhile, net immigration of Jews into Palestine was 216,000 for the period 1930-1939, and total Jewish immigration between 1919 and 1948 was 483,000.

Although the Jewish population rapidly increased, as did Jewish land holdings, the Arab population continued to grow even in areas with high Jewish populations. In fact the rate of increase in Arab population was greater in the regions with higher Jewish populations. This is undoubtedly because the urban areas populated by Jews were more affluent and afforded more employment opportunities, which also attracted Arabs from outside Palestine. This urbanization process does not abolish the reality of the evictions of Arab tenant farmers, who historically were “tied to the land” and owned the trees that were their livelihood. Foreign landowners did not respect these feudal traditions, and instead imposed an absolutist right to property over any supposed obligation to keep the peasants with the land. Arabs were displaced in the countryside, yet in the cities they grew in number alongside the Jews. Most of the Arab migrations were within Palestine; as we have seen above, less than a quarter of Arab population growth during the mandate period was due to foreign immigration.

The British mandate required the active involvement of Jewish organizations in establishing the new Jewish homeland. In 1929, a Jewish Agency was established for this purpose, and it was headed by the president of the World Zionist Organization, which dominated the Agency. The Jewish Agency established a welfare system and educational services, including Zionist control of Hebrew schools, and organized land purchases and urban development projects. Much of this organization was led by David Ben-Gurion, who imposed a socialist imprint on all of his projects, including an organized labor movement and a political party, the Labor Zionists. In 1920, he formed the Histadrut, a general union of Jewish laborers that provided social services and security, and training for immigrants. The Jewish economy became increasingly autonomous, and this was certainly by design, as Zionists had no intention of creating a joint society with the Arabs. As Ben-Gurion said in 1918: “We as a nation want this country to be ours; the Arabs, as a nation, want this country to be theirs.” The Zionists were quite conscious that there would be Arab resistance, as was natural, but this did not deter them from continuing the modern colonization of Palestine, as they saw the establishment of a Jewish homeland as a natural right and moral imperative. It was primarily left to the British, as guarantors of this Jewish homeland, to deal with Arab unrest as Jews continued to immigrate and purchase land. Indeed the British saw that Arabs were underrepresented in the mandate government, and no Arab was appointed head of a government department. Nonetheless, Zionist ideologues perceived many British functionaries as “pro-Arab” simply by virtue of being critical of Zionist policies, a rhetorical tactic pursued to this day. While both Arabs and Jews in the mandate government leaked information, Jewish espionage was much more thorough and organized, and they were able to smuggle stockpiles of weapons from the mandate government.

Land ownership was a critical point of contention between Arabs and Jews. With the advantage of immense foreign wealth brought in by Jewish organizations, Jews were able to purchase large tracts of land from absentee Arab owners. By 1948, they would own 20% of Palestine. The mandate’s Land Transfer Ordinance of 1920 prevented non-resident Arabs from purchasing land in Palestine, leaving the impoverished Palestinian Arabs at a serious competitive disadvantage. The ordinance did stipulate that after a land transfer, tenant farmers must be left with enough land for their sustenance. Jewish buyers evaded this requirement by asking Arab landowners to evict their peasants prior to sale.

Jewish land acquisition was mostly politically motivated; since only a small fraction of Jews farmed, there was little practical need for large land holdings. Arabs, on the other hand, apart from the insult to national pride of seeing Palestinian lands in the hands of foreigners, needed land for their sustenance as 90% of them were farmers. Under Ottoman rule, the Palestinian Arabs lived in an agrarian feudal society. The basis of their economy was now being threatened by politically motivated land acquisitions that evicted tenant farmers and often left nothing in their place. Some Jewish farmers did use Arab labor, but only for hire at low wages, not as tenants who were guaranteed housing and fields for their own sustenance. The peasant life was by no means idyllic, however, and as drought and economic depression made farming less profitable, Arab peasants voluntarily sold their lands to seek employment in the cities.

Most Jewish land was held by private capitalists, while about 4% was owned by the Jewish National Fund, established by the fifth Zionist Congress in 1901. Lands owned by the Jewish National Fund could never be sold, as they were to form the basis of a future Jewish state, and only Jews were permitted to work the land. Other Jewish landholders had no scruples about hiring Arabs, though they usually shared the Zionist rationale for land ownership, as evidenced by the relative lack of farming. Land was purchased in order to establish Jewish ownership of Palestine, not for any practical economic end.

The political ambitions of the Zionists were well known to the Arabs, and this naturally exacerbated tensions so that even a minor incident might spark a full riot. Emboldened Jews, for their part, expected their ascendant role to be respected by the British, and would violently protest any efforts to stifle the Zionist endeavor. These attitudes were powerfully expressed in the 1928-1929 Wailing Wall riots.

The Wailing Wall is not, as is commonly stated, a part of Herod’s Temple, but a western perimeter wall that partially surrounded the temple complex. The temple itself and all other buildings in the complex were completely destroyed by the Romans. Since the temple itself is no longer available for worship, the closest the Jews can come to venerating God’s house on earth is to approach this wall on Yom Kippur. The Temple Mount itself is occupied by the al-Aqsa mosque and the Dome of the Rock, and it is regarded by Muslims as a holy site, so non-believers are forbidden to enter.

Jews had long been permitted to pray at the Wailing Wall from outside the Temple Mount. In the 1920s, Jews made several attempts to purchase the wall, and some rightists openly advocated reclaiming the holy site, even rebuilding the temple. This development was paralleled among Arabs by a lower tolerance for Jewish worship at the wall, as it was now seen as an infringement of Arab ownership of the holy site. In 1928, Arabs complained of a Jewish prayer screen near the wall that blocked the street. British police removed the screen, resulting in brief mob violence and Jewish accusations of religious persecution. The following year, Arab rumors that Jews intended to seize the al-Aqsa mosque sparked violence by militant Muslims against Jews in Jerusalem and Hebron, killing 133. British police intervened belatedly, killing several dozen Arabs. While only a tiny minority of Arabs and Jews resorted to violence, nearly all saw the conflict over the Temple Mount as a political or nationalist issue rather than a purely religious one. Jews and Muslims had worshipped in and around the temple area for centuries, but only when the issue of land ownership came into play did violence flare.

The most significant uprising of the early mandate period was the “Arab Revolt” of 1936. An increasingly landless, proletarian Arab population turned to new political groups that preached defiance of the mandate government and the establishment of an Arab state. In 1935, a Jewish arms smuggling operation was exposed, prompting calls for a legislative council to address Arab concerns. The British parliament capitulated to Zionist objections to even this concession, igniting open revolt among Arab Palestinians.

In April 1936, Arabs united in a general strike against Jewish goods and services, and many committed acts of violence against Jewish settlers until November, when British forces quelled the revolt. In July 1937, the Peel Commission published a partition plan which would assign the fertile coast and Galilee to the Jews, leaving the West Bank and the Negev desert to the Arabs. Jerusalem and its environs would remain under a British mandate. This provoked a more furious Arab response, and the revolt continued with greater ferocity from 1937 to 1939, this time attacking British targets as well as Jews. The situation grew more chaotic as Arab peasants attacked landowning Arabs, and infighting developed among Arab leaders over whether to accept a partition of Palestine. The British retaliated ruthlessly, dynamiting houses of those suspected of harboring rebels (setting an ugly precedent for the Israelis), and hanging over 100 Arabs. In 1938, 1700 Arabs and 300 Jews were killed. The rebellion was crushed by early 1939, and the Arab population was left weak and leaderless.

As a result of the turmoil, a British commission of inquiry headed by Lord Robert Peel in 1937 recommended that Palestine be partitioned into Jewish and Arab states, with the ethnically heterogeneous zone from Jaffa to Jerusalem remaining under the British mandate and international control. The Jewish state would include Galilee and the Mediterranean coast, while the Arab state would include the present-day “West Bank” (historical Judea and Samaria) as well as the Negev desert to the south. The Peel Commission’s recommendations were accepted by Parliament, though both Arabs and Jews found grounds for objection.

For their part, Zionists made no secret of their expansionist desires, dreaming of a Jewish state covering all of Palestine and free of Arabs. Ben-Gurion sought to include Trans-Jordan in the Jewish state, expelling the Arabs there, while religious extremists hoped to rebuild the Temple. While these extreme views were the opinions of a minority, Jewish organizations were led by some of the more ambitious Zionists, whose influence was disproportionate to their number. In particular, the socialists, or Labor Zionists, though few in number, headed the best organized social and economic institutions, and were able to push their ideas through the British government.

One of the more striking examples of Zionist leverage was the suppression of the Passfield White Paper of 1930, which blamed Arab displacement on Jewish land purchases and the Zionist practice of hiring only Jewish labor. In view of the Balfour Declaration's requirement of “ensuring the rights and positions of other sections of the population,” Lord Passfield asked the Zionists to renounce some of their separatist policies. The response of world Jewry was to threaten Great Britain with a U.S. embargo. Prime Minister MacDonald capitulated completely, issuing a letter dictated by Chaim Weizmann, the former head of the World Zionist Organization, that rejected the Passfield White Paper.

This leverage, coupled with the influx of Jews from Poland and Germany that more than doubled the Jewish Palestinian population, enabled Zionists to continue to make bold claims that ignored the requirements of the Balfour Declaration. They allowed that the Arabs had a right to independence, but not in Palestine. The Jews, on the other hand, had an absolute right to an Israeli state that was not to be circumscribed by the rights of others. These were not new ideas, but an appeal to a pure nationalist Zionism that predated the Balfour Declaration and regarded the British mandate as both a vehicle and an obstacle to the realization of the state of Israel.

As the threat of war loomed over Europe, the British became increasingly anxious to secure the good will of the Arab peoples, whose lands were strategically necessary in a potential conflict with Germany. In May 1939, they issued a White Paper declaring that “the framers of the Mandate in which the Balfour Declaration was embodied could not have intended that Palestine should be converted into a Jewish state against the will of the Arab population of the country.” This was a direct blow to the Zionists, who explicitly sought a Jewish state with or without Arab consent. The White Paper instead envisioned a single Palestinian state which contained a “Jewish National Home,” with restricted immigration to 15,000 a year for five years, after which Arab consent was required. Jews already constituted over 30% of the Palestinian population at 467,000, 300,000 of whom had immigrated in the 1930s. The Jewish population had nearly tripled over the last decade, increasing by 180%, but this mass immigration was to be arrested immediately.

The idea that further immigration would require Arab consent would have been unacceptable to the Zionists in any scenario, but this came at an especially bad time, since the oppression of the Jews in central and eastern Europe made desirable an even greater increase in immigration to Palestine as a safe haven. The Zionists, despite their furious opposition to the 1939 White Paper, had little choice but to support Britain against the far greater evil of Nazi Germany.

When the Second World War began in Europe, it provided the occasion for the organization of an armed Jewish fighting force. The already existing Zionist defense force, the Hagana, helped train Jewish soldiers to fight alongside the British. Weizmann strenuously advocated for an all-Jewish brigade, a request that was begrudgingly conceded in 1944. Meanwhile, the Hagana accumulated stockpiles of weapons for use in a future war of independence against the Arabs and the British, if necessary. British officials, knowing the Zionists were preparing for an armed rebellion against British rule, raided several arms smuggling operations. Jewish leaders openly opposed these raids, showing their revolutionary intentions.

The Zionists also sought to undermine British policy through political means, as Weizmann lobbied through Jewish organizations in the United States. Americans were highly receptive to the more aggressive ambitions of the Zionists, and in 1944 both political parties agreed to support the creation of a “Jewish Commonwealth” after the war, effectively repudiating the 1939 White Paper. Despite this political success, Ben Gurion resisted any attempt to Americanize the Zionist movement, preferring instead to focus on direct military action to claim all of Palestine west of the Jordan, rather than negotiating a partition.

Complicating the situation, Jewish terrorist groups took matters into their own hands, succeeding only in alienating the British from the cause of a Jewish state. In the 1930s, the militant group Irgun had resorted to nakedly terrorist attacks against Arabs, and in 1939 began to fight the British in response to the White Paper. In 1940, they suspended anti-British activities in order to support the war effort, but some of them, led by former Hagana member Avraham Stern, insisted on continuing terrorist acts against the British. This splinter group of the Irgun was the notorious Stern Gang, which gave rise to the modern usage of the term “terrorism.” Stern was killed by British police in 1942, but some of his followers, including future Israeli prime minister Yitzhak Shamir, escaped from prison, and formed the LEHI (Fighters for the Freedom of Israel), which sought to assassinate British personnel. The Irgun, led by Menachem Begin (another future prime minister), resumed anti-British terrorist activities in 1943 as the German threat to Egypt subsided, but by a strange ethic, Begin directed that only the civilian government be targeted, in order to show continued support of the British military effort. Both Irgun and LEHI sought the establishment of a Jewish state over all of Palestine and Transjordan.

Jewish terrorism backfired in the short term, as the successful assassination of Lord Moyne in Cairo by LEHI served only to turn Winston Churchill away from the Zionist cause. Having been a friend of the assassinated deputy minister of the state, Churchill was determined that terrorism would not be rewarded, and he ended any discussion of the partition of Palestine or the establishment of a Jewish state for the remainder of his term. Before the House of Commons, he described Zionist militants in uncompromisingly harsh terms, saying, “if our dreams for Zionism are to end in the smoke of assassins’ pistols and our labors for its future to produce only a new set of gangsters worthy of Nazi Germany, many like myself will have to reconsider the position we have maintained so consistently in the past.” Zionist terrorist activities against the British ceased for the remainder of the war.

Palestinian Arab leadership had been in disarray since the Arab revolt of 1936-39. The nominal political and religious leader of the Arabs was Haj Muhammad Amin al-Husseini (1893-1974), who was appointed by the British as “Grand Mufti” (a novel title) in 1922. Al-Husseini was a poor choice for leadership, as he had been a provocateur of the 1920 attack against Jews at the Western Wall, and helped incite the riots of 1929. With the outbreak of World War II, al-Husseini disgraced himself further, appealing to the Axis powers to resolve the “Jewish question” in Palestine with the same brutal tactics employed in Europe. He spent most of the war in Germany, leaving the field open for other political leaders.

Al-Husseini’s Palestinian Arab party was singularly uncompromising in its position, opposing not only a Jewish state, but even a “National Home” within a united Palestine, as envisioned by the 1939 White Paper. Instead, there could only be an Arab government over all of Palestine. In al-Husseini’s absence, the de facto head of the party was Emile al-Ghuri, a Greek Orthodox, proving that Arab nationalism was not a purely Islamic concern. The Istiqal party was more moderate, endorsing the White Paper and approved of the creation of a Jewish National Home, though not a state.

In 1944, the Arab heads of state met in Alexandria, Egypt, calling for the establishment of a league of Arab states. They addressed the Palestine question in particular:

The Committee also declares that it is second to none in regretting the woes inflicted upon the Jews of Europe by European dictatorial states. But the question of these Jews should not be confused with Zionism, for there can be no greater injustice or aggression than solving the problem of the Jews of Europe by another injustice, that is, by inflicting injustice on the Palestine Arabs of various religions and denominations.

The Arab leaders strongly distanced themselves from the pro-Nazi stance of al-Husseini’s party, a racist position that was popular in Palestine, Iraq and Syria. Nonetheless, invoking the principle that injustice is not corrected by injustice, they opposed unlimited Jewish immigration to Palestine against the will of the Arab population, which is precisely what the Zionists sought, invoking the Holocaust as justification.

The Labour Party surprisingly defeated Churchill in 1944, making Clement Attlee Prime Minister of Great Britain. The Labour platform had endorsed a Jewish state and even the expulsion of Arabs across the Jordan, but geopolitical necessity soon induced the government to abandon the pursuit of a Jewish state, in order to win favor with the Egyptians. The British even refused to admit Jewish refugees to Palestine, causing the Zionists to turn to the United States for political support. Although the Americans were unwilling to amend their immigration laws to admit Jewish refugees into the U.S., President Truman did ask Attlee to permit 100,000 Jewish refugees to be admitted to Palestine. This request was denied, and Foreign Secretary Ernest Bevin expressed a position similar to that of Arab leaders, namely that the Jewish refugee problem was not to be mixed with the Palestine question.

Britain’s refusal to remove immigration restrictions or acknowledge the right to a Jewish state in even a part of Palestine naturally led to widespread Zionist outrage. In late 1945, David Ben-Gurion resorted to military measures, stockpiling arms supplied by wealthy foreign Jews, and using the Hagana to support the activities of the terrorist groups Irgun and LEHI. These groups assassinated British officers, soldiers, and police, bombed railways and took hostages. The British responded by raiding the Jewish Agency headquarters and arresting some of the Hagana leadership. This led to the infamous counter-response by Menachem Begin’s Irgun, which blew up the King David Hotel, killing ninety-one people on 22 July 1946.

As the mandate of Palestine was to be turned over to the United Nations, the British sought to achieve compromise by proposing an increase of Jewish immigration by 96,000 over two years, yet retaining a unified Palestinian state. Both sides were dissatisfied, as Ben-Gurion insisted on unlimited immigration while the Arabs wished to halt it altogether. The British turned over the matter to the United Nations in February 1947.

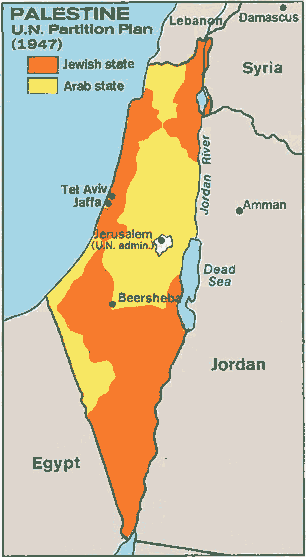

On 29 November 1947, the UN General Assembly voted 33 to 13, with 10 abstentions, to partition Palestine into Jewish and Arab states, with Jerusalem and its environs remaining under international control. Jewish Americans had been active in the U.S. and throughout the world in lobbying for the approval of this resolution, threatening boycotts and pressuring the U.S. government to exercise its influence over the votes of others. The result was quite favorable to the Jews in relation to the actual facts on the ground.

On 29 November 1947, the UN General Assembly voted 33 to 13, with 10 abstentions, to partition Palestine into Jewish and Arab states, with Jerusalem and its environs remaining under international control. Jewish Americans had been active in the U.S. and throughout the world in lobbying for the approval of this resolution, threatening boycotts and pressuring the U.S. government to exercise its influence over the votes of others. The result was quite favorable to the Jews in relation to the actual facts on the ground.

Shortly before the partition, Palestinian Jews numbered 608,000, or 32% of the total population of Palestine. Despite all of their massive land purchases over the past several decades, they owned only 20% of cultivable land and a mere 6% of the total area of Palestine, nearly all of which was along the coast or in Galilee. The UN partition plan, quite sensibly, assigned these areas to the future Jewish state, but more perplexingly, also gave to the Jews a huge swath of southern territory, including virtually the entire Negev, though Jewish landholdings in this area were miniscule. This had the effect of making the Palestinian state non-contiguous, separating the West Bank from the Gaza Strip. The Jewish state was also noncontiguous at two points, making the UN partition plan impracticable from the start.

The indefensible borders proposed by the partition plan would require an international presence to enforce the resolution. The Americans, however, were unwilling to have an international force deployed in Palestine, for fear that it would project Soviet influence in the region. The U.S. military was too weak to send its own forces, having demobilized down to prewar levels. Thus the British were left on their own to deal with an escalating cycle of terrorism.

Tragically, both the Jews and Arabs were led by their most extreme factions, those of Ben-Gurion and al-Husseini, neither of which recognized the right of the other nationality to exist in Palestine. Arab attacks on Jewish settlements were countered by the Hagana. The Jewish terrorist groups now directed their attacks against civilian Arab targets, indiscriminately killing women and children, and the Arabs responded in kind. Irgun and LEHI escalated their terrorist activity with a massacre of 250 people at Dayr Yasin on 9 April 1948. The bodies of men, women and children were thrown down wells, provoking terror throughout the Arab communities. As the Irgun drove out the Arab government of Haifa on 22 April and threatened further massacres, 300,000 Arabs fled within weeks.

In the wake of Arab flight, Jewish settlers overtook abandoned neighborhoods, in some cases leveling villages and replacing them with Jewish settlements. The Hagana repeatedly denied the requests of displaced Arabs to return to their homes weeks later, in contrast with later Israeli propaganda that the Arabs freely abandoned the land. Having consolidated control of all the territory assigned to the Jewish state by the UN partition except the Negev (where Jewish settlement was much too sparse), the establishment of the Israeli state was announced by David Ben-Gurion on 14 May 1948. A day later, the U.S. recognized Israel informally, while the Soviet Union was the first to formally recognize the fledgling state.

Immediately after Ben-Gurion’s declaration of an Israeli state, five Arab nations mobilized small armies to attack Israel. Contrary to popular legend, the Israelis were not outnumbered by a great margin, for the Zionists had over 20,000 armed fighters, while the combined armies of the five nations numbered 29,000: 11,000 from Egypt, 7,000 from Iraq, 5,000 from Jordan, 4,000 from Syria, and 2,000 from Lebanon. The attack on Israel was motivated by the mass expulsion of Arabs and the Israeli acquisition of territory belonging to the Arab partition, including western Galilee and the area surrounding Jerusalem. The UN was able to obtain a ceasefire from all parties on 11 June.

During the truce, the Israelis acquired weapons from Czechoslovakia, so when the Arabs resumed the war in July, they were routed by the better equipped and better organized Israeli forces. By the end of the year, the Israelis were able to secure their existing gains and invade the Negev all the way down to the Red Sea. The UN mediator, Count Bernadotte Folke, wanted the Israelis to relinquish the Negev and internationalize Jerusalem, but he was assassinated by Yitzhak Shamir's LEHI terrorists in September 1948. A truce was finally negotiated by the UN in 1949, with an armistice line recognizing all of Israel’s territorial gains, for the purpose of ending hostilities, not as an acknowledgement of their legitimacy. The Arabs reserved the right to recover conquered territory through diplomatic measures.

As a result of the war and ethnic expulsions of 1948, the de facto partition of Palestine was quite different from what the UN had resolved in 1947. The UN plan would have had a Jewish state covering 56% of Palestine (excluding Jerusalem) with a population of 498,000 Jews and 325,000 Arabs, and an Arab State covering over 43% of Palestine, with 807,000 Arabs and 10,000 Jews. Jerusalem, with a population of 100,000 Jews and 105,000 Arabs, would have been under international control. Instead, the Jewish state conquered 78% of Palestine, with a population of 600,000 Jews and 133,000 Arabs. A total of 727,000 Arabs were expelled from Israel, of which 470,000 entered refugee camps in the West Bank and Gaza Strip, while the remainder were repatriated to other Arab countries. If Israeli propaganda is to be believed, these 470,000 Arabs left their homes freely, preferring refugee camps to their native villages. Meanwhile, the Israelis redrew the map, abolishing Arab place names in favor of Hebrew names, in an attempt to extinguish the remnants of Palestinian Arab culture.

As a result of the war and ethnic expulsions of 1948, the de facto partition of Palestine was quite different from what the UN had resolved in 1947. The UN plan would have had a Jewish state covering 56% of Palestine (excluding Jerusalem) with a population of 498,000 Jews and 325,000 Arabs, and an Arab State covering over 43% of Palestine, with 807,000 Arabs and 10,000 Jews. Jerusalem, with a population of 100,000 Jews and 105,000 Arabs, would have been under international control. Instead, the Jewish state conquered 78% of Palestine, with a population of 600,000 Jews and 133,000 Arabs. A total of 727,000 Arabs were expelled from Israel, of which 470,000 entered refugee camps in the West Bank and Gaza Strip, while the remainder were repatriated to other Arab countries. If Israeli propaganda is to be believed, these 470,000 Arabs left their homes freely, preferring refugee camps to their native villages. Meanwhile, the Israelis redrew the map, abolishing Arab place names in favor of Hebrew names, in an attempt to extinguish the remnants of Palestinian Arab culture.

Although Ben-Gurion publicly distanced himself from the terror tactics used by Irgun and LEHI, the leaders of these groups were permitted to take seats in the Knesset (Israeli parliament) in 1949.

On 11 December 1948, the UN General Assembly passed Resolution 194, guaranteeing the Arab refugees’ right of return:

Resolves that the refugees wishing to return to their homes and live at peace with their neighbours should be permitted to do so at the earliest practicable date, and that compensation should be paid for the property of those choosing not to return and for the loss or damage to property which, under principles of international law or in equity, should be made good by the Governments and authorities responsible...

The resolution addresses Israeli security concerns by stipulating that only those Arabs willing to “live at peace with their neighbors” may return to their homes. However, even those who do not return must be compensated “under principles of international law or in equity,” that is, as a matter of right or entitlement. Israel has consistently flouted Resolution 194, though acceptance of the resolution was made a condition of its admission to the United Nations and international recognition as a state. The Israeli stance has been to maintain the absurd contradiction of forcibly preventing Arab refugees from repatriating, while claiming they are refugees by free choice.

On 11 May 1949, UN Resolution 273 was passed, recognizing the state of Israel and admitting it as a United Nations member, but with the understanding that Israel would implement the directives of the 1947 partition and Resolution 194 guaranteeing the right of return. Israel’s wholesale repudiation of these directives has led many Arab states to call for Israel’s expulsion from the United Nations, since it violated the conditions of admission and negotiated in bad faith. Ben-Gurion and his supporters considered themselves answerable to no one so they felt perfectly justified in disregarding international resolutions as they saw fit. This stance, called “Ben-Gurionism,” was an outgrowth of the ancient prejudice that Jews have no obligations to the Gentiles, and Ben-Gurion himself did not shrink from casting the question in such stark terms.

Ironically, Arab reaction to Israeli outrages actually contributed to the growth of the Israeli state, as over 300,000 Jews who were now persecuted in Arab countries immigrated to Israel, causing the Jewish population to swell above one million. The Israelis not only benefited from the additional population, but invoked these Jewish refugees as justification for denying the Arabs a right of return, instead proposing an exchange of populations.

The Israeli regime of Ben-Gurion established an aggressive security policy that entailed provocative offensive action in order to intimidate Arabs into accepting the Israeli state. Internally, this meant responding to Arab violence with a disproportionate response. In 1953, an Israeli woman and two children were killed by Arab terrorists, so Colonel Ariel Sharon was sent to the Arab village of Qibya in order to dynamite their houses as a punitive measure. Although the villagers were warned to flee, not all did so, and fifty people were killed. This policy of disproportionate collective punishment would become a hallmark of Israeli security doctrine, and the occasion of most of Israel’s war crimes.

Ben-Gurionists also favored aggressive posturing against Israel’s neighbors, provoking skirmishes on the Egyptian and Jordanian borders. Ben-Gurion’s chief of staff, Moshe Dayan, candidly admitted that this policy was a deliberate attempt “to maintain a high level of tension among our population and in the army. Without these actions we would have ceased to be a combative people and without the discipline of a combative people we are lost.” A starker contrast with UN Resolution 273’s declaration that Israel is a “peace-loving state” is scarcely imaginable.

Ben-Gurion retired from government in 1953, and the more dovish Moshe Sharett became prime minister. The defense minister, Pinhas Lavon, was a Ben-Gurionist hawk, who secretly created an Israeli spy ring in Egypt to sabotage the British military withdrawal from that country. Saboteurs would plant bombs at the British and American embassies and other buildings, killing Americans and Englishmen, while blaming the attacks on Islamic terrorists. Fortunately, the conspirators were captured before the plan could be carried out. At the time, the Israeli government denied involvement, though Lavon was forced to resign in disgrace. Israeli complicity in the terrorist plot was admitted in 1960.

In the wake of the Lavon scandal, Ben-Gurion returned as the Israeli leader and defense minister, and in February 1955 he attacked the Egyptians in Gaza, killing forty soldiers. This provocative action, supposedly in retaliation for Egypt’s execution of Jews falsely accused of terrorism (when in fact the plot was real), was actually a continuation of the Ben-Gurionist policy of intimidation. These offensive tactics created a new enemy for Israel in Gamal abd al-Nasser, the new ruler of Egypt who had hitherto been preoccupied with domestic concerns. Nasser now turned to Soviets to purchase modern armaments with which to confront Israel. He formed a defense pact with Syria in October, prompting Israel to attack Syria in December, killing fifty-six. The raids on Gaza and Syria were condemned by UN Resolutions 106 and 111 respectively. Syria became more closely allied with Egypt as a result of the attack, and increased its purchases of Soviet arms.

Israel’s opportunity to invade Egypt arose in 1956, when Nasser nationalized the Suez Canal, prompting the British to consider aggressive action in order to secure their strategic interests. Israel had already been plotting an invasion with the French, who supplied fighter jets and other armaments. Britain, France and Israel conspired in October to invade the Sinai peninsula, which Ben-Gurion believed should belong to Israel, and then to publicly call for a ceasefire, with forces withdrawn to opposite sides of the canal, effectively allowing Israel to occupy the peninsula. If Nasser objected, he could be portrayed as rejecting peace, and the attack could continue.

This amoral scheme was implemented on 29 October, when Israeli forces invaded the Sinai peninsula. Two days later, the English and French demanded that Nasser withdraw behind the Suez. Nasser naturally refused to relinquish the Sinai, so the allies were given their desired pretext for further aggression. The British bombed Egyptian air fields, and the Egyptians were forced to withdraw from the Sinai. On 5 November, British and French forces attacked the canal, abandoning their public pretense of neutrality. The clumsy conspiracy resulted in the blockage of transit through the canal for months.

The Eisenhower administration pressured British prime minister Anthony Eden to abandon then invasion, and the U.S. voted with the majority of the UN to condemn all three nations for their aggression. The Suez affair discredited Eden’s government, and the prime minister resigned on 9 January 1957. His 1977 obituary in the London Times famously remarked that “he was the last prime minister to believe Britain was a great power and the first to confront a crisis which proved she was not.” Israel was forced to withdraw from Egyptian territory, but with the condition that the Gaza Strip and the straits of Tiran at the mouth of the Gulf of Aqaba (important to Israeli commerce) be monitored by international forces rather than Egypt.

The Suez crisis was not the only factor causing Israel’s enemies to multiply. In 1964, Israel began to divert water from the Sea of Galilee to a canal that would irrigate the Negev, thereby diminishing the water supply of Syria, Lebanon and Jordan. Syria responded with its own plan to divert the Jordan to Syria, but Israeli bombers destroyed construction equipment in 1966.

Meanwhile, the newly-formed Fatah terrorist organization, whose leaders included Yasser Arafat, conducted dozens of attacks against Israeli targets, leading to the Israeli response of demolishing entire villages in the West Bank, which was controlled by Jordan. Despite the Jordanian government’s efforts to disrupt Fatah, Israel held Jordan responsible for the attacks, in an attempt to justify its brutal reprisals.

Despite these new threats, Israeli domestic politics moved away from the overt militarism of Ben-Gurion. When the Lavon affair was investigated anew in 1960, Ben-Gurion attempted to protect Moshe Dayan, his chief of staff, and Shimon Peres, his defense minister, from being implicated in the botched sabotage conspiracy. Resentful that all blame was being pinned on him, Lavon accused Dayan and Peres of complicity in the conspiracy. The Israeli cabinet, led by finance minister Levi Eshkol, exonerated Lavon in Ben-Gurion's absence. In this he was joined by Golda Meir, a Ben-Gurion favorite appointed as foreign minister in 1956. Eshkol, Meir, and Lavon all shared a deep distrust of excessive military control of Israeli politics, as represented by Dayan and Peres.

Partially in reaction to this shift in his own cabinet, Ben-Gurion resigned as prime minister in 1963, to be replaced by Eshkol. In 1965, Eshkol and Meir formed a coalition with the Ahdut Ha’Avodah (Unity of Labor) party, against Ben-Gurion’s wishes. Ben-Gurion left the Mapai (Labor) party that had dominated Israeli politics since the founding, and formed his own Rafi (workers’) party with Dayan and Peres. Mapai still won the 1965 elections, even without some of Israel’s most prominent figures. The war heroes of 1948 and 1956 were in the Rafi party, making Mapai now seem “soft” by comparison. The militarist camp would exploit this perception in 1967.

The second-largest political party in Israel by 1955 was the Herut party led by Menachem Begin, former leader of the Irgun terrorist group that attacked British civilian targets in the 1940s, including the King David Hotel. Begin, now posturing as a legitimate politician, still called for the Jewish conquest of all of Palestine and Jordan. Although Ben-Gurion refused to acknowledge Begin as a legitimate statesman, Eshkol actually worked to rehabilitate Irgun’s image, an astonishing position for one supposedly soft on security. There really was no dovish party in Israel; there were only degrees of militarism, and differences of opinion on how independent the civilian government should be from military influence.

Begin’s ultranationalist, anti-socialist Herut party was not able to mount a substantial opposition to Mapai until 1965, when it merged with the Liberal Party to form the Gahal bloc, nearly doubling its electoral representation. The unified “Alignment” of the Labor (Mapai) and Unity of Labor parties won 45 seats in the 1965 elections, while Gahal won 26, the then-moderate National Religious Party won 11, and Ben-Gurion’s Rafi party won 10.

Superpower involvement in the Middle East contributed greatly to preparing the conditions for another Middle East conflict. In 1960, the Americans discovered Israel’s secret Dimona nuclear reactor. President John Kennedy took a tough non-proliferation stance, demanding full inspections of Israeli nuclear capability. Aid to Israel was mostly non-military under Kennedy, with the exception of a few antiaircraft missiles. Kennedy also increased economic aid to both Israel and Egypt. This evenhanded policy was discarded by Kennedy’s successor, Lyndon Johnson, who was naïvely pro-Israeli, fully accepting the myth of an embattled frontier people defending themselves from marauders. Under Johnson, aid to Israel increased dramatically, and included formidable offensive military capability, including 250 tanks and 48 attack aircraft in 1965-66, the first time the U.S. provided offensive weaponry to Israel. Whereas Kennedy had made limited arms deals conditional upon nuclear inspections, Johnson turned a blind eye to the Israeli nuclear program. Meanwhile, U.S. aid to Egypt declined and finally ended in early 1967. The U.S. did provide military aid to the Arab kingdoms of Jordan and Saudi Arabia, as a defense against the Soviet client states of Egypt, Syria and Iraq. Israel’s espionage agency Mossad exploited the Johnson administration’s obsession with communism by giving exaggerated reports of the Soviet threat in the Middle East.

In reality, Soviet policy in the Middle East was relatively moderate. While providing military and economic aid to Egypt, Syria, and Iraq, the Soviets actually allowed these countries to suppress their domestic Communist parties. Khrushchev’s policy was not a principled attempt to spread Marxism, but a pragmatic effort to reduce U.S. influence in the region. Ironically both superpowers meddled in the region not with the prospect of concrete gain (for neither was dependent on oil imports at the time), but to prevent the aggrandizement of the other. Were there not so many lives lost as a result of this meddling, the situation would be comic.

Pursuant to their policy of deterrence, the Soviets counteracted U.S. support of Israel, exploiting the Arab possession that Israel was in collusion with the U.S. in order to win influence in the Middle East. The USSR vetoed a condemnation of Syrian guerrilla attacks by the UN Security Council, and delivered massive quantities of armaments to Egypt, Syria and Iraq. These weapons, unlike Israeli warplanes, were of limited offensive capability, due in part to the inability of the Arab countries to incorporate sophisticated weaponry into their relatively poorly trained armies. The Soviet, American, and Israeli governments were all fully aware of Israel’s clear military superiority, but this did not prevent Nasser and other Arab leaders from becoming overconfident.

In 1967, the Arab terrorist organization Fatah increased its attacks on Israel, attempting to provoke an international crisis. Border clashes with Syria continued, and the Syrian president Nureddin al-Atassi openly called for a war of liberation of Palestine, provoking a stern warning of retaliation by Eshkol. Al-Atassi was only a figurehead president; the real ruler of Syria was General Salah Jadid, who encouraged Fatah to raid Israel from the Syrian border, though most Fatah attacks continued to be based in Jordan. The USSR, now ruled by Brezhnev, did not have direct involvement with Fatah, and the Soviet premier even condemned the militant Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO).

The PLO had been formed in 1964 by the Arab League, in an attempt by Nasser to claim ownership of the Palestine issue. The PLO’s “national charter” advocated armed struggle against Israel in order to return all of Palestine to Arab control, with Jews existing only as a Palestinian minority. This position was rightly perceived by Israelis as a denial of Israel’s right to exist. In keeping with Nasser’s pan-Arabism, the charter did not try to invent a new “Palestinian” nationality, but declared that “Palestine is an Arab homeland,” and “Palestinians are those Arab citizens who were living normally in Palestine up to 1947,” as well as “Jews of Palestinian origin” who “are willing to live peacefully and loyally in Palestine.” The PLO’s charter was the obverse of the extreme Zionist position held by Begin’s Herut party.

The terrorist activities of the PLO and Fatah were usually conducted through the Jordanian border, against the will of King Hussein of Jordan, who saw the groups as threats to his regime. The Israelis were aware of this distinction, as they secretly negotiated for peace with Hussein while taking counter-terrorist measures in the West Bank. The most notable of these reprisals occurred in November 1966, when Israel responded to the death of three soldiers in a mine explosion by invading the West Bank town of Es Samu, which was populated by 4,000 Palestinian refugees. Using tanks and paratroopers, the Israelis blew up at least fifty houses and several public buildings, including the town’s only clinic. A Jordanian platoon engaged the Israelis, suffering at least fifty fatalities.

Israel’s actions were condemned by UN Security Council Resolution 228, which warned, “if they are repeated, the Security Council will have to consider further and more effective steps as envisaged in the Charter to ensure against the repetition of such acts.” Even the Johnson administration was outraged by Israeli actions, for not only had Israel made clear its territorial ambitions, but the attack also undermined the credibility of Hussein’s regime, which the U.S. had supported at great expense as a bulwark against Arab radicalism. When war came in 1967, King Hussein would be under tremendous pressure to join the conflict if he wished to preserve his government, as his kingdom, including the occupied West Bank, had a 60% Palestinian Arab population.

The first skirmishes that directly led to the Six-Day War occurred on 7 April 1967, when a typical border skirmish on the Golan Heights was escalated by Syria’s deployment of six warplanes, which were shot down by Israel. The Israeli fighters defiantly continued to fly over Damascus. Enraged by this aggressive taunt, the Syrians conferred with the Egyptians and suspected that the CIA was plotting with Israel to topple their regimes. Border clashes continued until, on 12 May, Israel threatened massive retaliation, including the overthrow the Syrian regime. This threat appeared to confirm Arab suspicions of a U.S.-Israeli plot, and the impression was reinforced by the Soviet Union’s false intelligence that “large forces” had been mobilized by Israel on the Syrian border. On the basis of Israel’s verbal threats and supposed military deployment, Nasser sent troops into the Sinai peninsula on 14 May.

As a result of the 1956 conflict, the Sinai peninsula had been occupied by the United Nations Emergency Force (UNEF) to serve as a buffer, while recognizing Egyptian sovereignty. On 16 May, Nasser asked UNEF to withdraw, as UN General Secretary U Thant recognized was his right, and on 18 May, Nasser formally requested the full withdrawal of UNEF from the entire peninsula. UNEF offered to serve as a buffer on the Egyptian-Israeli border, but Israel declined. Controversially, Nasser reoccupied the straits of Tiran on 21 May, and more aggressively, blocked transit through the straits the following day, sealing off the Gulf of Aqaba. This crippling of Israeli commerce had been a cause of the 1956 war, so the overconfident Nasser was foolish to believe that Israel would not attack this time. Making matters worse, on 25 May the Egyptian war minister deceived Nasser by claiming that the Soviets supported his aggression, when in fact they were urging restraint.

On 27 May, the Israeli cabinet voted not to go to war, acceding to President Johnson’s urging to allow him two weeks to get the Egyptians to re-open the straits. Meanwhile, on 30 May, Jordan signed a defense pact with Egypt, placing the Jordanian army under Egyptian command, in clear anticipation of a coordinated war from at least two fronts. Egypt’s allies, Jordan and Syria, were enemies of each other, making the triple alliance unwieldy from its inception.

Fearing that a Johnson peace mission would avert war, the Israeli military asserted itself, demanding that Eshkol appoint ministers from the right-wing parties. On 1 June, the prime minister conceded, appointing Moshe Dayan as minister of defense and Menachem Begin as minister without portfolio, all but guaranteeing that there would be war.

On 2 June, Nasser agreed to send his vice president to Washington in order to negotiate the re-opening of the straits of Tiran. In order to deny Nasser a diplomatic victory, the Israeli cabinet resolved to strike while the pretext for war, the blockade of the straits, still existed. As in 1956, the blockade was merely an opportune excuse to pursue a war of aggression that Israeli generals had long desired. Now, with ultranationalist expansionists in the cabinet, war was a foregone conclusion. Still, the Israelis sought confirmation that the U.S. would condone such a war, and agents in the CIA and Department of Defense indicated to Mossad that they would be glad to see the Arabs’ Soviet armaments destroyed, as that could damage Soviet influence throughout the world.

On 4 June, Eshkol’s cabinet approved Moshe Dayan’s plan to attack Egypt the following morning. Within hours, most of the Egyptian air force in the Sinai was destroyed on the ground by Israeli fighters. On the same morning, Jordanian forces took posts in the Arab sector of Jerusalem, and commenced shelling of West Jerusalem, which had been claimed by Israel since the 1949 armistice. Israel responded by invading East Jerusalem and the West Bank.

The UN Security Council immediately called for a ceasefire, but the Arab states unwisely refused, which suited Israeli plans perfectly. The Israelis had been lobbying the U.S. to postpone any cease-fire until after Israel was able to “finish the job,” a ploy they would use repeatedly in the future, in order to create facts on the ground in lieu of diplomacy. The game was to occupy as much territory as possible before the Arab states accepted a ceasefire.

On 7 June, Israel conquered Old Jerusalem and the West Bank all the way to the Jordan River, until Jordan declared acceptance of a ceasefire. The Straits of Tiran were occupied by Israel the same day. On 8 June, Egypt accepted a ceasefire, but Israel’s ambitions had not yet been satisfied, as Dayan planned to occupy the entire Sinai peninsula and attack Syria.

A major international incident occurred when the Israelis attacked the American surveillance ship USS Liberty. On the morning of 8 June, the ship had been spotted by an Israeli reconnaissance aircraft, and reported to naval headquarters. After looking up the hull markings in a Janes manual, naval officers identified the craft as the Liberty, and since it was an intelligence ship, forwarded the report to naval intelligence. Meanwhile, at least eight further reconnaissance flights were sent to the Liberty’s position. At 2:00 in the afternoon, Israeli fighters bombarded the Liberty with rockets, cannon fire, and napalm, knocking out the communications antenna, command bridge, and machine guns, killing eight crewmen. Shortly afterward, three Israeli torpedo boats fired five torpedos and thousands of machine gun rounds into the Liberty, killing another 26 crewmen. The torpedo boats even fired on life rafts. A total of 34 were killed and 173 wounded out of a crew of 294.

The Israelis immediately claimed the incident was a tragic accident, though the Liberty was clearly marked in Roman letters (not Arabic), flew a large American flag, and signaled “U.S. ship” to the torpedo boats. Moreover, contrary to Israeli reports, it was moving at only 5 knots before the attack and did not at all resemble the silhouette of an Egyptian supply ship. Nonetheless, Johnson accepted the Israeli version of events, and the incident was declared an accident by the official U.S. naval report without any congressional inquiry. Even on the assumption of an accident, there would almost certainly have been gross negligence and disregard for human life on the part of the attackers who failed to identify their target or those who relayed orders or reports, but an Israeli judge implausibly dismissed all such claims as lacking sufficient merit for a trial, so no one was ever so much as reprimanded for the incident. Israel eventually paid $13 million in reparations. Still, the official U.S. response to this incident is in stunning contrast to its usual severity (compare the Maine or Gulf of Tonkin incidents). The USA’s “special relationship” with Israel had been forged, even if it was not always reciprocated.

Shortly after midnight on 9 June, the Syrians accepted a cease-fire, though they had not done much fighting. Israel had not accomplished its objectives, however, so the army in the Sinai continued all the way to the Suez Canal. Dayan ordered an assault on Syria, which Eshkol approved after the fact and encouraged to proceed deeper into the Golan Heights. Having fully secured the headwaters of the Jordan on 10 June, Israel ended its opportunistic war of conquest.

Shortly after midnight on 9 June, the Syrians accepted a cease-fire, though they had not done much fighting. Israel had not accomplished its objectives, however, so the army in the Sinai continued all the way to the Suez Canal. Dayan ordered an assault on Syria, which Eshkol approved after the fact and encouraged to proceed deeper into the Golan Heights. Having fully secured the headwaters of the Jordan on 10 June, Israel ended its opportunistic war of conquest.

Israel’s territorial gains in the Six-Day War changed the parameters of the Arab-Israeli conflict. Previously, Nasser and other Arab leaders called for a return to conditions before the 1948 war, meaning either the 1947 UN partition or a unified Palestine under majority Arab rule. Now, their diplomatic efforts were directed toward a restoration of the 1949 armistice line, or the “pre-1967 border,” as it now came to be known. The Israelis, for their part, were buoyed by what seemed to be a providential victory, and were loath to relinquish their new territories, especially the West Bank, which was the Biblical Judea and Samaria. Although the Israeli government told the U.S. they would relinquish the Golan and the Sinai in exchange for demilitarization, this position was soon retracted in favor of permanent occupation of the Golan.

The Arab heads of state met in Khartoum, Sudan after the war and resolved to work diplomatically toward Israeli withdrawal from occupied territories, without recognizing Israel or directly negotiating with Israel. This policy of non-recognition enabled Israelis to extend a fictitious olive branch, by inviting Arabs to direct negotiations while refusing third-party negotiations. In this way, the Israelis could disingenuously claim that they were waiting by the phone but the Arabs would not call.

On 22 November 1967, the UN Security Council passed Resolution 242, which emphasized “the inadmissibility of the acquisition of territory by war and the need to work for a just and lasting peace in which every State in the area can live in security,” and called for:

The resolution also affirmed the necessity of “achieving a just settlement of the refugee problem,” and “guaranteeing the territorial inviolability and political independence of every State in the area, through measures including the establishment of demilitarized zones.”

This seemingly unequivocal call for Israel to withdraw from the occupied territories in exchange for peace and recognition of its right to exist actually had some deliberate points of ambiguity. The Israelis wanted to retain at least some of the newly occupied territories in a final settlement; in fact, they already declared that East Jerusalem was non-negotiable. Thus the resolution’s clause on Israeli withdrawal was amended from “the territories” to simply “territories,” allowing for the possibility that a final settlement might result in slightly different borders than the 1949 armistice. The Israelis would later exploit this loophole in order to claim permanent rights to most or even all of the West Bank. The original draft required both Israeli withdrawal and Arab recognition of Israel “without delay,” but the final draft set no timetable or sequence of reciprocating acts.

Resolution 242 would be the basis of all future international efforts to resolve the Palestinian issue, but its terms would be routinely hedged or even flouted by both sides. The Arabs, for their part, refused to recognize Israel, while the Israelis flouted the principle of the inadmissibility of territorial conquest by claiming large tracts of land far beyond what “secure borders” could credibly require. The real motivation for this territorial ambition was nationalistic, religious and economic. The West Bank was the ancient land of Israel, while the Golan secured the Jordan’s headwaters and the Sinai provided oil fields and an outlet to the Red Sea. The status quo after 1967 favored Israel, leaving little incentive to negotiate in good faith with the Arab nations.

Yasser Arafat’s Fatah organization found a safe haven in Jordan, from where they launched attacks against Israeli military targets. In early 1968, the Israelis invaded Jordan, but received heavy casualties from the Palestinian resistance. Fatah’s enhanced prestige proved fateful, as the PLO decided to allow the guerrilla groups to be represented in its leadership. As Fatah was the most popular of these groups, Arafat became head of the PLO in February 1969.

The newly radicalized PLO had its charter revised in 1968, now declaring that “Armed struggle is the only way to liberate Palestine,” and “Commando action constitutes the nucleus of the Palestinian popular liberation war.” The new charter also rejected “all solutions which are substitutes for the total liberation of Palestine” and “all proposals aiming at the liquidation of the Palestinian problem, or its internationalization.” The 1968 charter retained the uncompromising positions of the 1964 version, repudiating the 1947 UN partition, the Balfour Declaration and the British Mandate. Both the 1968 charter and the original characterize Zionism as “racist,” “aggressive,” “expansionist,” and “fascist,” and regard Judaism as a religion, not a nationality. Having no national identity of their own, the Jews “are citizens of the states to which they belong.”

The PLO’s position was unequivocal. All of Palestine would yield to Arab rule by armed force. As Zionism was thoroughly repudiated, Judaism was not a nationality. Only those Jews of descent predating the Balfour Declaration were Palestinians; the others were citizens of the country from which they came. It is only understandable why the Nixon administration did not attempt to negotiate a peace agreement with the PLO as representatives of the Palestinian people. Although Fatah enjoyed popularity among Palestinians living in Jordan and Syria, Arabs in the West Bank generally did not share the PLO’s radical position, and most would have been content with a settlement that allowed them to own their land and return to their homes.

Arafat’s Fatah party was challenged within the PLO by the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP), which had close ties with the Syrian regime. Within a year of its formation, the groups Jibril and Popular Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PDFLP) splintered from the PFLP. These groups had strong Marxist leanings, and usually advocated the overthrow of Arab monarchs such as Hussein of Jordan. They became internationally notorious in 1968 when Jibril and the PFLP hijacked Israeli planes. The Israelis responded by destroying thirteen Arab civilian airliners in Beirut, holding the Lebanese responsible for the attacks. This blatant war crime outraged the Lebanese, who went into civil war over the Palestinian issue as well as inter-confessional rivalries. Until then, Lebanon had normal relations with Israel, but Zionist aggression now created a fourth border enemy for the Jewish state. The embattled Maronite Catholic government unsuccessfully attempted to suppress PLO activities in Lebanon, and finally recognized PLO autonomy over refugee camps in Lebanon and paths to the Israeli border.

Nasser immediately began rebuilding the Egyptian military to pre-war levels, and sought to provoke international intervention with limited strikes on Israeli targets in the Sinai. Israel responded by building fortifications along the Suez and occupying the west bank of the canal. Nasser had reluctantly accepted Resolution 242, agreeing to recognize the Israeli state de facto in exchange for full withdrawal from the peninsula. Israel refused Egyptian overtures for third-party negotiations, wishing to retain some of the Sinai for itself. Now the Egyptians escalated the shelling, only to have their air defense systems wiped out by the Israelis by July 1969.

The Nixon administration proposed a settlement that would require mutual recognition of sovereignty and Israeli withdrawal from nearly all of the Sinai. The Israeli government, now headed by Golda Meir after Eshkol’s death, rejected the proposal, and escalated bombing raids against Egypt, resulting in many civilian casualties. The Israeli ambassador to the U.S., Yitzhak Rabin, claimed he had American approval for the destruction of the Egyptian military.

In 1970, the Soviets re-armed Nasser, and even provided their own combat pilots. Israel now agreed to a U.S.-brokered ceasefire that acknowledged Resolution 242 as the basis for further negotiations, only after they were persuaded that this would not require full withdrawal to pre-1967 borders.

The Kingdom of Jordan had claimed the West Bank as its own territory since the 1948 war, so King Hussein was wary of the Palestinian nationalists, many of whom advocated an independent Palestinian state. After the 1967 war, many of these militants retreated to Jordan proper, the “East Bank,” where they ruled as local warlords and launched raids against the Israelis. Israel retaliated by destroying civilian targets in Jordan.

In June 1970, the PFLP fought Jordanian forces and took Western hostages, forcing Hussein to make changes in his cabinet in appeasement of PFLP demands. Hussein’s willingness to recognize Israel in exchange for withdrawal was unacceptable to the militant Palestinian groups, who wished to claim all of Palestine for an Arab state. The PFLP and PDFLP openly called for Hussein’s overthrow. In September, the PFLP hijacked four airliners, and Hussein once again acceded to their demands. After the hostages were released, Hussein embarked on a war against the Palestinians on 16 September.

Over 3000 were killed and 11,000 in the Jordanian civil war, which lasted less than ten days. Most casualties were noncombatant Palestinians in refugee camps. Syria intervened early in the conflict with a tank strike against Jordan. The U.S. had deployed its Mediterranean fleet as an empty bluff, being unprepared for entering the conflict. Israel offered air support in case the Jordanian air force failed, but this proved unnecessary. The Jordanians won a clear military victory. Despite this success, King Hussein was pressured by other Arab leaders to give formal recognition of the PLO as the leaders of the Palestinian people.

Conflict between Jordan and the Palestinian groups erupted again in July 1971, resulting in the expulsion of their leadership to Lebanon. Groups within the PFLP and Fatah sponsored terrorist attacks against Israelis, while the Israelis employed equally ruthless “commando” tactics. “Commandos,” as they are known in Britain and Israel, or “special forces,” as they are called in the U.S., are soldiers trained for assassination and sabotage, often employing tactics identical to those of terrorists. Israeli commandos would kill PLO leaders in their homes, sometimes using car bombs and letter bombs. The most notorious case of Arab terrorism in this period was the kidnapping of eleven Israeli athletes at the 1972 Munich Olympics. A failed German rescue attempt resulted in the killing of all the hostages. The perpetrators were a Fatah group called Black September, after the Jordanian civil war.

Nasser died in 1970, to be succeeded by Anwar al-Sadat as president of Egypt. In 1971, Sadat accepted a UN peace proposal for full Israeli withdrawal, demilitarization of the Sinai, Egyptian recognition of Israel, and Israeli use of the Suez Canal. The Israelis rejected the peace plan, since several cabinet members wished to retain Sharm al-Shaykh at the straits of Tiran, and a roadway connecting it to Israel.

U.S. Israeli relations strengthened as Henry Kissinger took over the Nixon administration’s Middle East policy in 1971. Kissinger viewed the Arab-Israeli conflict pragmatically in a Cold War context. Determined that the U.S. should dominate the region, he opposed State Department attempts to broker an Egyptian-Israeli peace until Egypt would end its Soviet patronage. Meanwhile, the U.S. continued to supply Israel with warplanes, in an attempt to win Jewish votes in the 1972 election.

Sadat ordered all Soviet military advisers to leave Egypt in July 1972. Despite Egypt’s rejection of Soviet support, Kissinger made no serious efforts to revive the Egyptian-Israeli peace process even after Nixon was re-elected, being content with the status quo. Sadat turned to the Soviets again in February 1973, receiving antiaircraft weaponry and offensive military hardware.