There was no global warming from 2001 through 2009, yet we are now told that this past decade was the warmest on record. Both assertions are factually correct, though they paint very different pictures of the state of the world’s climate.

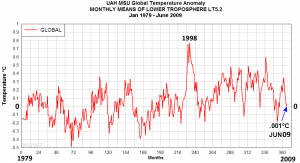

As we can see in the above graph, 1998 was an unusually hot year (due to “El Niño”) compared with the previous decade, followed by an uncharacteristically cool 1999. Temperatures rose in 2000 and 2001, short of the 1998 peak, yet higher than the average for the 1990s. From 2001 through 2009, the annual global mean temperature anomaly remained about the same, within measurement error. The media likes to publish things like “this was the third hottest year on record,” but such year-to-year rankings are meaningless, as they are distinguished only by statistical noise. Scientists know better than that, yet NASA researchers have often played a media game where they announce that a given year is on track to be the hottest on record. In mid-2005, for example, NASA announced that the global temperature was on track to surpass the 1998 record. Such a distinction is meaningless, since the temperatures were about the same, within the accuracy of the models.

Note we do not measure the average global temperature, but a temperature anomaly, or change with respect to some baseline. In absolute terms, the average surface temperature of Earth is about 15 degrees Celsius, a figure that is only accurate to a full degree. It is impossible to come up with an accurate global mean temperature in absolute terms, due to the lack of weather stations in regions such as oceans and deserts, which magnifies the overall uncertainty. How then, can we come up with more accurate measurements of global temperature change?

First, a baseline period is chosen. A common choice is the period from 1951-1980, which was relatively cool compared to the decades before and after. The graph shown uses 1961-1990 as a baseline, and many current measurements use 1971-2000, since there is more data for this period. For each temperature station or location, we compare the current measured temperature with the average measurement at that station over the baseline period, and the difference is called the “anomaly”; really, simply an increase or decrease with respect to our arbitrary norm (i.e., the baseline). We can measure each local temperature anomaly to the accuracy of the thermometer, and climate scientists maintain that interpolating the anomaly between stations creates little error, since temperatures tend to rise and fall in a region by about the same amount, and the mean temperature anomaly is accurate to 0.05 degrees C. This is more accurate than any individual measurement, due to the error propagation of averages, which adds in quadrature, so the error in the mean is less than the error of any individual measurement.

This assessment of the accuracy depends on the assumption that our weather stations are a fair representative sample of global climate, and that our interpolations over local regions are valid and accurate. Logically, we cannot know the actual global temperature increase or decrease any more accurately than we know the global mean temperature: i.e., within 1 degree Celsius. What we call the “global mean temperature anomaly” is really a weighted average of all measurement stations, which we assume to be a representative sample of the entire globe. Strictly speaking, this is not the same as “how much the temperature increased globally”.

In fact, it is arguable that the notion of “global temperature” is a will-o’-the-wisp. The atmosphere is in constant thermal disequilibrium, both locally and globally, making it practically, and even theoretically, impossible to have a well-defined temperature at any point in time, since the notion of temperature presumes a large-scale equilibrium. Even if we could integrate the momentary temperature over time at a given point, the “average” value we get would not at all be representative of the actual temperature, since more time is spent near the extremes than at the average. This is why we take the maximum and minimum temperatures of each 24-hour period (the daily “high” and “low”) as our data set for each measurement station. There is also the difficulty that surface temperature varies considerably from 0 to 50 feet above sea level, and there is no rigid definition of the altitude at which “surface temperature” should be measured. This introduces the real possibility of systematic error, and makes our assessment of the accuracy of the mean anomaly somewhat suspect.

Let us assume, for the sake of argument, that mean temperature anomaly really is accurate to 0.05 degrees Celsius. Then if 2005 was 0.75 degrees Celsius above the 1950-1980 average, while 1998 was 0.71 Celsius above average, it is statistically meaningless to announce that 2005 was the hottest year on record, since we do not know the mean temperature anomaly accurately enough to know whether 1998 or 2005 was hotter.

All of the foregoing deals with straight temperature records, not adjusting for anything except regional interpolation. However, there are many tricks – not falsifications, but misleading portrayals – one can perform in order to paint the picture you wish to show. For example, you can subtract out natural oscillations caused by things like El Niño, volcanic explosions, and variations in solar irradiance, to show what warming would have occurred without these natural effects. This methodology can be dubious, for you are subtracting natural cooling effects without subtracting potential warming effects that may be coupled to them.

There was dramatic global cooling in 2007, driven by strong La Niña conditions (the decrease in solar activity that year was not enough to account for the cooling). The cooling trend continued in 2008. Although the stagnation in annual mean temperature throughout the decade is still consistent with the hypothesis of long-term anthropogenetic global warming, some climate scientists recognized that this presented bad PR for their views, and reacted accordingly.

In October 2009, Paul Hudson of the BBC (an organization generally sympathetic to the AGW hypothesis) wrote that there was no warming since 1998. This was a fair and accurate presentation of reality, as climate scientists privately admitted. According to the infamous East Anglia e-mails, even the strident advocates of the AGW hypothesis acknowledged that there was a lack of warming. In response to the Hudson article, Kevin Trenberth wrote: “The fact is that we can’t account for the lack of warming at the moment and it is a travesty that we can’t.” Tom Wigley disagreed that the lack of warming was unexplainable, yet even he admitted there was a lack of warming:

At the risk of overload, here are some notes of mine on the recent lack of warming. I look at this in two ways. The first is to look at the difference between the observed and expected anthropogenic trend relative to the pdf [probability density function] for unforced variability. The second is to remove ENSO [El Niño Southern Oscillation], volcanoes and TSI [Total solar irradiance] variation from the observed data.

Both methods show that what we are seeing is not unusual. The second method leaves a significant warming over the past decade.

Wigley is basically saying that if certain natural variable factors were removed, there would have been warming. However, these variations actually did occur, so there was not actually warming. Wigley shows how the lack of warming might be explained by other factors, yet he does not deny the fact that, in actuality, there was no warming.

It is very dubious to play this game of “what would have happened” in climate history, since all atmospheric events are interconnected in a chaotic flux, making it impossible to cleanly subtract out an effect as if it were an autonomous unit. This is why analysis trying to show what percent of warming is caused by which effect is really unhelpful. I have little confidence in the ability of climate scientists to make long-term predictions about chaotic systems with insanely complex oceanic and biological feedback. From my recollections at MIT, those who majored in earth and atmospheric sciences weren’t the most mathematically gifted, so I doubt that they’ve since managed to work such a mathematical miracle. It is hardly encouraging that climate scientist Gavin Schmidt claimed that the Stefan-Boltzmann constant should be doubled since the atmosphere radiates “up and down”! I don’t fault James Hansen for erroneously predicting to Congress in 1989 that there would be a decade of increased droughts in North America. What is objectionable is when such a claim is presented as the only scientifically plausible inference. I know that CO2 is a greenhouse gas, and that it should cause warming, all other things being equal, but all other things aren’t equal.

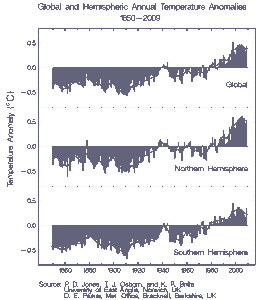

What do we know, then, if anything? The graph below shows a five-year moving average of the global mean temperature anomaly. (The moving average is to smooth out irregular spikes.)

From this graph, several distinct periods can be discerned with regard to temperature trends.

1860-1900: constant to within +/- 0.1 deg C.

1900-1910: dropped to 0.2 deg C below the 1860-1900 average.

1910-1940: warmed 0.5 deg C from 1910 low, or 0.3 deg C above 1860-1900 avg.

1940-1950: dropped 0.2 deg C from 1940 peak, or 0.1 deg C above 1860-1900 avg.

1950-1975: stable to within 0.1 deg C (that’s why it’s used as a baseline); in 1975, 0.2 deg above 1860-1900 avg.

1975-2000: 0.5 deg warming, or 0.7 deg above 1860-1900 avg.

2001-2009: constant

So, there were thirty years of warming (1910-1940) 0.5 deg, then a cooling/stable period (1940-1975); then another twenty-five years of warming (1975-2000) 0.5 deg. This is quite different from the popular conception of monotonic, geometrically increasing temperature (i.e., “the hockey stick,” which makes clever choices of start date, zero point, and axis scale). There were actually two periods to date of dramatic global warming: 1910-1940 and 1975-2000. This rudimentary analysis already suggests that anthropogenetic effects on climate are more subtle and complex than a simple greenhouse effect.

Looking at this graph, we are right to be skeptical about Arctic ice cap alarmism. We have only been measuring the Arctic ice cap since 1979, which coincides with the start of the last great warming period. We do not, then, have an adequate long-term view of the cap, and cannot reliably extrapolate this extraordinary warming period into the future. Predictions of a one to three meter sea level rise, displacing hundreds of millions people, such as that infamously made by Susmita Dasgupta in 2009, ought to be put on hold for the moment. An imminent climate disaster is always coming but never arrives. Just read the prophecies of imminent doom, flood and drought from the 1980s, or go back decades earlier to read the predictions of a new ice age.

In order to make the current warming seem even more catastrophic, many climate scientists have seen fit to rewrite the past, going so far as to deny the Medieval Warm Period, which is abundantly well established by the historical record. In their perverse epistemology, contrived abstract models with tenuous suppositions should have greater credibility than recorded contemporary observations. There is no getting around the fact that Greenland and Britain had much more inhabitable and arable land than at present. A more plausible hypothesis is that the Medieval Warm Period was not global, yet this too is increasingly refuted by paleoclimatic evidence.

I find that the importance of observed global warming is diminished, not enhanced, by excessive alarmism and overreaching. Short of an Arctic collapse – improbable, since the ice cap is much more advanced now than in the medieval period – we are left with the projection that global temperature may increase as much as a full degree C by 2100, with a probable sea level increase of about a foot: bad, but not cataclysmic. Of course, that doesn’t get you in the top journals or on government panels.

I’ve noticed that in physics, where things really are established to high degrees of certainty and precision, no one ever says “the science is overwhelming”. It is only when the science is not so “hard,” as in the life, earth, and social sciences, that you need to make repeated appeals to authority. When the science truly is overwhelming, the evidence speaks for itself, and no polls need to be taken.

Update – 14 Oct 2010

One of the last of the WWII-era physicists, Harold “Hal” Lewis of UC-Santa Barbara, has raised an animated discussion with his letter of resignation to the American Physical Society, contending that the APS has been complicit in the “pseudoscientific fraud” of global warming, and the Society has suppressed attempts at open discussion. He invokes the ClimateGate e-mails as evidence of fraud, and attributes the lack of critical discourse to the abundance of funding opportunities for research supporting the global warming hypothesis.