Overview

Introduction [of Document]

Chapter I: Catholic Principles on Ecumenism

Chapter II: The Practice of Ecumenism

Chapter III: Separated Churches and Ecclesial Communities

1: The Eastern Churches

2: Churches and Ecclesial Communities in the West

Together with Lumen Gentium and Orientalium Ecclesiarum, the decree on ecumenism titled Unitatis Redintegratio establishes the Second Vatican Council’s position on the Church’s relation to other Christians. The present document presumes familiarity with the Church’s constitution as described in Lumen Gentium. Whoever ignores or misrepresents that document will likely end up in confused error when interpreting this one. The vision of Catholic ecumenism outlined in Unitatis Redintegratio is markedly distinct from the loosely defined ecumenical movement

of the post-Conciliar period in many respects. There is no hint of religious indifferentism or suppression of Catholic doctrine in any of the decree’s pronouncements. The fact that such tendencies have come to be identified with the ecumenical movement only proves that there is a need for Catholics to regain familiarity with the authentically Catholic ecumenism taught by the Council.

The first important clarification needed is that ecumenism, as understood in Unitatis Redintegratio, applies only to Christians. It is not a generic term for good relations with people of other religions, which are to be discussed later in Nostra Aetate. Ecumenism is specifically Christian, as it comes from Christ’s wish that all who believe in him should be gathered into one flock. This wish is both a reality and an aspiration:

Christ the Lord founded one Church and one Church only. However, many Christian communions present themselves to men as the true inheritors of Jesus Christ; all indeed profess to be followers of the Lord but differ in mind and go their different ways, as if Christ Himself were divided. Such division openly contradicts the will of Christ, scandalizes the world, and damages the holy cause of preaching the Gospel to every creature. (UR, 1)

Although the one Church founded by Christ retains the fullness of unity (as expounded in Lumen Gentium), there are many other communions of Christian believers who live in division, contrary to Christ’s will. This division is a scandal to the rest of the world, since it cannot discern which Church or communion is the true inheritor of Christ, and perceives only a dismembered body whose parts are in opposition to each other. Sectarian strife, viewed from the outside, can make Christianity seem to be an incoherent and uncharitable religion, thereby undermining the preaching of the Gospel.

In recent times, many separated Christians have developed a longing for the restoration of unity among all Christians. They profess their Christian faith individually and as corporate bodies.

For almost everyone regards the body in which he has heard the Gospel as his Church and indeed, God’s Church. All however, though in different ways, long for the one visible Church of God, a Church truly universal and set forth into the world that the world may be converted to the Gospel and so be saved, to the glory of God. (UR, 1)

Every Christian thinks of his communion as being the Church of God. The Council does not confirm this belief, for that would contradict its previous assertion that Christ established only one Church. Rather, this belief is itself evidence that all Christians yearn to belong to the one visible and truly universal Church of God. This Church, the Council has said in Lumen Gentium, is the Catholic Church. (LG, 8) The Council does not repeat the teaching here, for it has already declared its teaching on the Church.

(UR, 1)

The above account of ecumenism describes the perspective of separated Christians, since the ecumenical movement existed only among Protestants prior to the Council. In the decree that follows, the Council will set before all Catholics the ways and means by which they too can respond to this grace and to this divine call.

(UR, 1)

Christ’s desire for unity is expressed explicitly in his prayer: that they all may be one; even as thou, Father, art in me, and I in thee, that they also may be one in us, so that the world may believe that thou hast sent me.

(John 17: 21) Through the Eucharist, the unity of His Church is both signified and made a reality.

(UR, 2) Christ also promised his followers that he would send forth his Spirit, and this Spirit gathered all believers into one Church, with one faith and one baptism. Thus the Apostle says that all who have been baptized have put on Christ and are one in Christ Jesus. (Gal. 3:27-28)

Here the Council is speaking of the time shortly after the Ascension, when all believers belonged to the one Church of Christ. Yet we can already anticipate some implications for the ecclesiology of the later Church, as we notice that the unifying sacraments of the Eucharist and baptism are found even outside the visible structure of the Catholic Church. Most importantly, the Holy Spirit, who is the principle of the Church’s unity,

bestows grace even outside the visible Catholic communion, impelling separated Christians toward unity.

In order to establish this His holy Church everywhere in the world till the end of time, Christ entrusted to the College of the Twelve the task of teaching, ruling and sanctifying. Among their number He selected Peter, and after his confession of faith determined that on him He would build His Church. (UR, 2)

Christ established the Church to last forever, entrusting its governance to the apostles and building it upon Peter, with Christ Himself as the cornerstone. He entrusted to Peter all His sheep… to be confirmed in faith, and shepherded in perfect unity.

This government was passed on to their successors:

Jesus Christ, then, willed that the apostles and their successors—the bishops with Peter’s successor at their head —should preach the Gospel faithfully, administer the sacraments, and rule the Church in love. It is thus, under the action of the Holy Spirit, that Christ wills His people to increase, and He perfects His people’s fellowship in unity: in their confessing the one faith, celebrating divine worship in common, and keeping the fraternal harmony of the family of God. (UR, 2)

Here it is clear that Christ’s will for His Church’s unity is expressed in the government of the apostles and their successors, headed by the successor of Peter. It is only in this structure that Christian unity is perfected. We are undoubtedly here speaking of the Catholic Church, not only before divisions arose, but as it exists visibly today:

The Church, then, is God’s only flock; it is like a standard lifted high for the nations to see it: for it serves all mankind through the Gospel of peace as it makes its pilgrim way in hope toward the goal of the fatherland above. This is the sacred mystery of the unity of the Church, in Christ and through Christ, the Holy Spirit energizing its various functions. (UR, 2)

Note the use of the present tense: the Church is God’s only flock. The one flock is not something that ceased to exist, but continues even today. It is not an abstraction, but something visible to all nations. This exclusivist claim for the Catholic Church does not come out of nowhere, but is consistent with all previous Catholic teaching, as well as that of Lumen Gentium. While the Church is the one flock, nonetheless, the Council will expound how other Christians still remain in imperfect communion with this one Church founded by Christ upon Peter.

Even in the beginnings of this one and only Church of God there arose certain rifts, which the Apostle strongly condemned. But in subsequent centuries much more serious dissensions made their appearance and quite large communities came to be separated from full communion with the Catholic Church—for which, often enough, men of both sides were to blame. (UR, 3)

The Church of God is a historical entity, as shown by this text placing it in concrete history. Rifts or separations from this Church, being contrary to Christ’s desire for unity, are condemned by the Apostle. (1 Cor. 1:11, 11:22) Clearly the Council, citing the Apostle as condemning even these early rifts, also considers the later more serious dissensions

to be a sin against Christian unity. The dissenters, in their act of separation, lose the unity which remains in the Catholic Church as something she can never lose. (cf. UR, 4) Thus we find a consistent asymmetry in the Council’s language: other churches and communities are said to lack full communion with the Catholic Church, but the Catholic Church is never said to be deficient in its communion toward other Christian communities. This is because every authentic impetus toward Christian unity must lead toward communion with the one flock established by Christ and entrusted to the apostles and their successors, headed by the successor of Peter.

Although there is an asymmetry between the Catholic Church and other Christians with respect to ecclesial unity, it does not follow that all blame for separation rests on the dissenters. The Council says, often enough, men of both sides were to blame.

Even the most devout Catholic apologist may acknowledge that there have been historical instances where Catholics effectively drove away their brethren from Christian unity by being unduly severe or by giving scandal. To give an example of undue severity, the papal legates sent by Leo IX to Constantinople in 1054 were needlessly offensive and hostile, showing no reverence to the patriarch or metropolitans, and actively attacking Greek customs rather than simply defending Latin customs. This behavior alienated the Greek hierarchy, squandering whatever slight possibility there may have been of reconciling with the obstinate, ambitious patriarch Michael Cerularius. As an example of scandal, surely none is greater than that occasioned by the sacking of Constantinople in 1204 by Crusaders and Venetians. This event arguably did more to ensure continued Greek hostility and mistrust toward Latin Christendom than any theological or canonical controversy.

While the original schismatics or dissenters may have had only a share of the blame for events leading to separation, those of later generations have no formal culpability at all.

The children who are born into these Communities and who grow up believing in Christ cannot be accused of the sin involved in the separation, and the Catholic Church embraces upon them as brothers, with respect and affection. For men who believe in Christ and have been truly baptized are in communion with the Catholic Church even though this communion is imperfect. (UR, 3)

This is the decree’s first important advancement in the Church’s position on ecumenism. For the first time, the Church explicitly teaches that Christians born in separated Churches or communities are not thereby guilty of the sin of separation. This was always in fact the case, since personal sin is not passed by propagation. Still, this declaration is significant because of its implication for the relation of such Christians to the Catholic Church. They are perceived not as opposing or moving away from the Catholic Church, but as being raised in a state of imperfect communion they did not create. Barring some culpable personal act of unjust hostility to the Church, they may be regarded positively as Christian brethren, rather than negatively in terms of the schismatic acts of their ancestors.

The basis of this positive regard for separated Christians is their faith in Christ and true baptism, for all who have been justified by faith in Baptism are members of Christ’s body.

(UR, 3) Yet Christ’s body is the Church, the only concrete realization of which is the Catholic Church. Thus all baptized Christians in some way pertain to the Catholic Church, or are in communion

with it, as the Council says. We must keep in mind that being in communion

is a much more intimate relation than mere association or similarity. The baptized are really incorporated into the Church on some level, and so by the same token the Church has a responsibility for all Christians. Her pastors cannot ignore or disregard them, if they are to emulate the Good Shepherd.

The Church has always recognized the indelible character of baptism, never allowing it to be repeated, and has also considered it the means by which we are made members Goof the Body of Christ. (cf. Council of Florence, Session VIII) These long acknowledged truths are pregnant with paradox, as they imply that those Christians visibly separated from the Catholic Church are nonetheless joined to her in a real way. Unitatis Redintegratio draws out this implication explicitly, and attempts to describe what is meant by such imperfect communion.

The Council candidly acknowledges that there are obstacles to full communion with the Catholic Church, caused by differences in doctrine, discipline, and ecclesiology. These obstacles, however serious, do not abolish the fact that the separated communities have members who deserve to be called Christian and are to be accepted as brethren by Catholics, insofar as they are all justified by faith in baptism. (UR, 3)

Apart from this minimal condition of Christian brotherhood, the various communities may share other gifts of the Church to varying degrees of perfection.

Moreover, some and even very many of the significant elements and endowments which together go to build up and give life to the Church itself, can exist outside the visible boundaries of the Catholic Church: the written word of God; the life of grace; faith, hope and charity, with the other interior gifts of the Holy Spirit, and visible elements too. All of these, which come from Christ and lead back to Christ, belong by right to the one Church of Christ. (UR, 3)

Here we have a concrete enumeration of some of the elements of sanctification

mentioned in Lumen Gentium. As all such elements belong to the one Church of Christ, which implies that the various Christian communities have some participation in the gifts of the one Church.

Now, this ecclesiological statement admits of orthodox and heterodox interpretations. The orthodox interpretation, consistent with perennial Catholic teaching, including that of Lumen Gentium and more recently, Dominus Iesus (2000), is that the Catholic Church is the sole historical entity that can claim to be the Church of Christ, while other Christians are sanctified to the extent that they are in imperfect communion with the Catholic Church, and thus partake of some of the gifts entrusted to her. The heterodox interpretation, explicitly rejected in Article 8 of Lumen Gentium, is that the visible, hierarchical Catholic Church and the heavenly Church of Christ are two distinct entities. In that view, the quotation above would be misinterpreted to mean that the separated Christians receive their gifts by virtue of belonging to some mystical, invisible Church of Christ

that is united only on a spiritual plane, and they have no need of the Catholic Church.

Thankfully, we do not need to guess about which is the correct interpretation, not only because of the clarification in Dominus Iesus, but also because the text of Unitatis Redintegratio itself resolves the matter.

For it is only through Christ’s Catholic Church, which isthe all-embracing means of salvation,that they can benefit fully from the means of salvation. We believe that Our Lord entrusted all the blessings of the New Covenant to the apostolic college alone, of which Peter is the head, in order to establish the one Body of Christ on earth to which all should be fully incorporated who belong in any way to the people of God. (UR, 3)

Since the Catholic Church alone is the all-embracing means of salvation

(generale auxilium salutis, following an expression used by the Holy Office in 1949), it is only through this Church that other Christians may fully benefit from the gifts they have. All the blessings of the New Covenant are entrusted to the Apostolic College alone, headed by Peter. Whence it follows that whatever blessings are found among other Christians are received through the Catholic Church, which contains the rightful successors of Peter and the apostles. This is only logical and consistent with the decree’s earlier assertion that there is only one flock, as well as with the supposition that Christ’s will for the Church’s unity is not an idle wish, unessential to salvation. In short, whatever salvific activity is present in other Christian communities comes from their imperfect communion with the Catholic Church.

With this in mind, we can readily understand what the Council means when it says:

…the separated Churches and Communities as such, though we believe them to be deficient in some respects, have been by no means deprived of significance and importance in the mystery of salvation. For the Spirit of Christ has not refrained from using them as means of salvation which derive their efficacy from the very fullness of grace and truth entrusted to the Church. (UR, 3)

As evidence of salvific agency in separated churches, the Council notes that some non-Catholics retain many liturgical actions of the Christian religion.

Here the Council undoubtedly has in mind, first and foremost, the valid Eucharist found among the Orthodox, which surely is not without salvific benefit. Thus such liturgical actions are generally regarded as capable of giving access to the community of salvation.

The community of salvation is the Church, so these salvific liturgical actions are evidence of communion with the one Church and participation in her unique mission of salvation. Again, the Council explicitly states that whatever is salvific in the other communities derives its efficacy from the fullness of grace and truth entrusted to the Church.

Since only the Catholic Church possesses this fullness of grace, as discussed above, it follows unequivocally that the Church

here is the Catholic Church.

The separated churches and communities remain deficient in various respects, most notably in unity. Note that the Council says only that our separated brethren, whether considered as individuals or as Communities and Churches, are not blessed with that unity which Jesus Christ wished to bestow on all those who through Him were born again into one body.

It does not say that the Catholic Church lacks unity. Although the various types of Christians are all born again into one body by baptism, they still lack the unity that Christ willed for all believers, but is only realized in the Catholic Church. Ecumenism, then, takes on the character of an imperative to obey Christ’s will and bring all Christians into catholic unity.

There are several concrete initiatives for promoting Christian unity enumerated by the Council:

These are: first, every effort to avoid expressions, judgments and actions which do not represent the condition of our separated brethren with truth and fairness and so make mutual relations with them more difficult; then,dialoguebetween competent experts from different Churches and Communities. At these meetings, which are organized in a religious spirit, each explains the teaching of his Communion in greater depth and brings out clearly its distinctive features. In such dialogue, everyone gains a truer knowledge and more just appreciation of the teaching and religious life of both Communions. In addition, the way is prepared for cooperation between them in the duties for the common good of humanity which are demanded by every Christian conscience; and, wherever this is allowed, there is prayer in common. Finally, all are led to examine their own faithfulness to Christ’s will for the Church and accordingly to undertake with vigor the task of renewal and reform. (UR, 4)

Here we find the basic outline of the Vatican Council’s plan for ecumenism. The first point, suppression of certain expressions, judgments and actions

that complicate ecumenical relations, is perhaps the most visibly implemented in the modern Church. The language of post-Conciliar Catholic writing is markedly different from the pre-Conciliar period. Gone are the severe condemnations and stern assertions of authority, replaced by fraternal exhortations and sympathy for human weakness. This is not to say that the content of teaching has changed or been softened, though sometimes this appearance can be given, but rather the pastoral approach has changed, treating democratic man with the dignity he expects, and engaging people of other beliefs on equal terms. This respectfulness is not grounded in a supposed equality between truth and error, but in the dignity of human persons as such. Further, it is not motivated merely by the desire to be diplomatic, but also to represent actual conditions accurately. For example, we now avoid calling other Christians heretics

or schismatics,

not because we doubt the material heresy of their doctrines or the objective fact of schism, but because we recognize that the present generation of separated Christians does not necessarily bear culpability for their errors, which are often held in good faith (bona fides). This consideration can be found in Catholic teaching well before the Council, but only now does it receive the prominence it deserves.

The second point, ecumenical dialogue among experts, is hardly less public, but it only involves relatively few members of the Churches or communities involved. It is essential that this be a dialogue, where both parties respectfully hear each other instead of merely asserting what they believe. The purpose of such dialogue is to gain a greater appreciation of the other’s perspective, so the obstacles to unity are more accurately perceived. In this way, genuine disagreements can be distinguished from misunderstandings, and each side may explain the reasons for their position, in a fraternal and non-polemical tone. The immediate purpose of such dialogue is not to convert the other party, but at least to persuade them of one’s reasonableness and good will, as well as to highlight shared values, in order to facilitate working for common goals.

This leads to the third point, where communions in ecumenical dialogue act cooperatively for the common good, and may even pray in common. Although ecumenical meetings are organized in a religious spirit,

the Council does not seem to envision a specifically religious course of cooperative action, instead making a vague call to work for the common good.

Lastly, ecumenism also entails that each community of Christians should look to renew and reform itself in order to better obey Christ’s will for all his flock to be united. In the Catholic Church, this imperative informed the post-Conciliar reform of liturgy and catechesis, which removed or de-emphasized elements that might lead to hostility toward other Christians.

The ultimate goal of ecumenism is the reunion of all Christians into the unity that the Catholic Church alone possesses:

…when the obstacles to perfect ecclesiastical communion have been gradually overcome, all Christians will at last, in a common celebration of the Eucharist, be gathered into the one and only Church in that unity which Christ bestowed on His Church from the beginning. We believe that this unity subsists in the Catholic Church as something she can never lose, and we hope that it will continue to increase until the end of time. (UR, 4)

Consistent with what we have said so far, the Council denies any ecclesiology that would claim the Church lost her unity centuries ago and hopes to regain it in the future. Rather, this unity, bestowed on the Church from the beginning, subsists in the Catholic Church as something she can never lose.

The Catholic Church has never lost the unity that Christ bestowed on His Church; hence she alone can properly claim to be the one flock. This is not to deny that there are Christians outside the visible structure of the Catholic Church, but rather they belong to the one flock to the extent that they are in imperfect communion with the Catholic Church.

By analogy with similar expression in Lumen Gentium, we understand this unity subsists in the Catholic Church

to mean that the Catholic Church is the concrete subject of the unity that characterizes Christ’s Church. Since Christ has only one Church, it follows that no other entity besides the Catholic Church can be the subject of this unity. Indeed, Unitatis Redintegratio nowhere attributes this unity to any but the Catholic Church. Thus, the only way to partake of Christian unity is by participation in the Catholic Church.

What does it mean for the Church’s unity to increase

? In the Latin text, it is clear that ‘unity’ and not ‘Catholic Church’ is the antecedent of that which is to be increased. The word translated as increase

is crescere, literally, to grow.

The Latin term more clearly indicates that we are speaking primarily of an increase in extension, not in intensity. Indeed, the Catholic Church already possesses the most perfect degree of unity, but she may nevertheless grow in extent, bringing others into communion. Yet, for the separated Christians, it is possible for unity to increase even in degree. This is because unity is conceived in terms of communion, which admits varying degrees of perfection. The Council hopes that unity will continue to increase,

suggesting it has already been increasing. This has been most obviously true in the extensive sense, as the Catholic Church had expanded greatly in the preceding centuries. Yet it is also true to some extent in the intensive sense, as the ecumenical movement was itself a sign of various Christian denominations becoming more oriented toward ecclesiastical unity.

The Catholic hope for the eventual union of all Christians does not imply that ecumenism is just another word for conversion: …when individuals wish for full Catholic communion, their preparation and reconciliation is an undertaking which of its nature is distinct from ecumenical action. But there is no opposition between the two, since both proceed from the marvelous ways of God.

(UR, 4) Ecumenism does not mean preparing other Christians to convert to Catholicism. It is an altogether different operation, consisting of real dialogue on equal terms without predetermined outcomes. This does not justify the opposing error of thinking that inviting Christians into full communion with the Church is anti-ecumenical.

Ecumenism does not require us to be content with a permanent stasis of friendly disunity. The same Holy Spirit that implores us to be charitable to fellow Christians also wills for us to be united as one flock. It is therefore impossible for the Church’s missionary activity to be intrinsically opposed to true ecumenism, if we acknowledge that Christ wills for His Church to be one.

Catholics should pray for their separated brethren, keep them informed about the Church, and make the first approaches toward them.

(UR, 4) Though such action is to be undertaken with the attentive guidance of their bishops,

this is nonetheless a remarkable shift in attitude by the hierarchy. Previously, Catholics had been frequently warned not to fraternize with heretics, lest their own faith should be jeopardized. Indeed, the primary significance of excommunication is to exclude someone from the society of the Church for the good of the faithful. While this caution was sound advice when dealing with those who have formally defected from the Church, it is less applicable in circumstances where non-Catholic views are held bona fide, and there is no animus toward the Catholic nor any desire to ruin his faith. Since these social circumstances had become prevalent in much of the modern world, the Council judiciously encouraged Catholics to make general overtures to their brethren, while leaving doctrinal dialogue to the experts.

The primary ecumenical duty of Catholics, however, is to is to make a careful and honest appraisal of whatever needs to be done or renewed in the Catholic household itself, in order that its life may bear witness more clearly…

(UR, 4) This call to spiritual reform and renewal does not indicate that the Church is defective:

For although the Catholic Church has been endowed with all divinely revealed truth and with all means of grace, yet its members fail to live by them with all the fervor that they should, so that the radiance of the Church’s image is less clear in the eyes of our separated brethren and of the world at large, and the growth of God’s kingdom is delayed. All Catholics must therefore aim at Christian perfection and, each according to his station, play his part that the Church may daily be more purified and renewed. (UR, 4)

One way for Catholics to give a better witness to Christian teaching is to let charity prevail in all things,

preserving unity only in essentials.

With this broadmindedness, Catholics better express the universality of the Church, admitting diversity in spiritual life, discipline, liturgy, and even in their theological elaborations of revealed truth.

Openness within the Church, keeping infighting to a minimum, will help attract others to Christian unity and remove needless obstacles imposed by historical or cultural accidents.

This greater charity should be extended even to the traditions of separated communities. It is right and salutary to recognize the riches of Christ and virtuous works in the lives of others who are bearing witness to Christ, sometimes even to the shedding of their blood.

Recognizing that there are authentic works of the Holy Spirit among non-Catholic Christians, the Council adds:

…anything wrought by the grace of the Holy Spirit in the hearts of our separated brethren can be a help to our own edification. Whatever is truly Christian is never contrary to what genuinely belongs to the faith; indeed, it can always bring a deeper realization of the mystery of Christ and the Church. (UR, 4)

A Catholic should not reject any part of the Church’s spiritual treasury simply because it arose among separated Christians. If it is of orthodox faith and an authentic work of the Spirit, it deserves to be praised, and we may benefit from it. Here, of course, some discernment is needed, so such charity presumes a well-formed Catholic conscience, as well as guidance by the magisterium.

The principle that whatever is done truly in Christ’s name is not opposed to the faith can be found in the Gospel of Mark, where John tells Jesus of another exorcist: Master, we saw one casting out devils in thy name, who followeth not us, and we forbade him.

(Mk. 9:37) Jesus replies: Do not forbid him. For there is no man that doth a miracle in my name, and can soon speak ill of me. For he that is not against you, is for you.

(Mk. 9:38) All good works, great or small, done in Christ’s name, are in favor of Christ and His Church. For whosoever shall give you to drink a cup of water in my name, because you belong to Christ: amen I say to you, he shall not lose his reward.

(Mk. 9:40) Note the expression, because you belong to Christ,

indicating that the separated Christian is rewarded precisely because he honors the apostolic Church. This is consistent with the Vatican Council’s ecclesiology, where the sanctifying elements among the separated brethren are gifts proper to the Catholic Church.

The division among Christians affects even the Catholic Church:

…the divisions among Christians prevent the Church from attaining the fullness of catholicity proper to her, in those of her sons who, though attached to her by Baptism, are yet separated from full communion with her. Furthermore, the Church herself finds it more difficult to express in actual life her full catholicity in all her bearings. (UR, 4)

Here the term ‘Church’ again clearly applies to the Catholic Church, as the text speaks of those attached to her by Baptism, yet separated from full communion with her,

obviously referring to non-Catholics. Yet, strikingly, the Council also says the Church has not attained the fullness of catholicity proper to her.

Again, as with the increase in unity,

we have an apparent paradox. On the one hand, catholicity is proper to

the Catholic Church, as expressed in her name and as indicated in the marks of the Church of the Creed, which Lumen Gentium identifies with the Catholic Church. On the other hand, the Church is prevented from attaining the fullness of catholicity.

Does this imply a defect?

The Church is catholic or universal in the sense that she contains absolutely all the faithful, and is not confined to any one country or class of men, but embraces within the amplitude of her love all mankind, whether barbarians or Scythians, slaves or freemen, male or female.

(Catechism of Trent, The Creed, Article IX) The Catholic Church is clearly universal in this visible sense, but also in a deeper sense of containing all the faithful who have existed from Adam to the present day, or who shall exist, in the profession of the true faith, to the end of time.

(Loc. cit.) The catholicity of the Church is intimately bound to her status as the exclusive means of salvation. Thus it is something already perfectly guaranteed by Christ, and not something that can admit of any defect or deficiency.

The Church on earth is governed by a visible hierarchy, headed by the successor of Peter, who has universal jurisdiction over all the faithful. In practice, however, many Christians do not acknowledge this jurisdiction, and have broken communion with the Catholic Church to varying degrees. This does not diminish the catholicity of the Church in the sense of her universal mission, as she still reaches out to all nations, and has a global extent unmatched by any other Christian communion. Nor does she cease to contain all who are saved, for any separated Christians who are saved receive their reward by honoring the Church through which all saving grace comes.

Rather, the fullness of catholicity

is compromised in the plain sense that the Church’s universal jurisdiction is not acknowledged by all Christians. This is indicated by the qualifying phrase: in those of her sons who, though attached to her by Baptism, are yet separated from full communion with her.

That is to say, the Church’s catholicity is deficient only in separated Christians, so this is not a deficiency in the Church as such, but in the imperfect communion of the separated Christians.

When proposing specific actions to implement principles of ecumenism, the Council ranks first and foremost those which pertain to Church renewal. Every renewal of the Church is essentially grounded in an increase of fidelity to her own calling.

(UR, 6) The Church, in her dimension as a human institution, may need to correct deficiencies in moral conduct or in church discipline, or even in the way that church teaching has been formulated—to be carefully distinguished from the deposit of faith itself…

The Council does not specify exactly how the formulation of doctrine is distinct from the deposit of faith. Obviously they are not identical, yet the official formulas of doctrine are guaranteed to be free from error, so they cannot be deficient in the sense of being erroneous. Rather, they might be deficient in a relative sense, as not fully expressing the reality signified. By this standard, all human formulations of doctrine are deficient, since our concepts are only imperfect images of the realities they represent, and so there may be some aspects of reality that they ignore or de-emphasize. An authentic theological renewal, therefore, would consist not in the denial of the truth of traditionally formulated teaching, but in complementing the traditional formulas with other expressions, which accentuate aspects of divine revelation that have not been fully captured or expressed by the older formulas.

Among the renewal activities oriented toward ecumenism, the Council enumerates: Biblical and liturgical movements, the preaching of the word of God and catechetics, the apostolate of the laity, new forms of religious life and the spirituality of married life, and the Church’s social teaching and activity…

(UR, 6) Reforms in these areas had already taken place in the years preceding the Council, and these are pledges and signs of the future progress of ecumenism.

The soul of the ecumenical movement, according to the Council, is a spiritual ecumenism

which is a reform of the heart. This requires the grace to become self-denying, humble, gentle in the service of others, and to have an attitude of brotherly generosity towards them.

(UR, 7) At its core, ecumenism entails a change in interior disposition toward one of greater humility, charity, and service toward others. Instead of boasting of the greater graces they have received, Catholics should humble themselves to engage other Christians as equals. Instead of polemically denouncing all other forms of Christianity, Catholics are called to recognize what is good in other Christian traditions, and to acknowledge that not all errors are culpable, while at the same time faithfully representing the truth of Catholic tradition. Most importantly, we must recognize that the gifts of the Church are ordered not so that we may lord them over others, but to dispose us for the service of others. It is in this sense that Catholic triumphalism

has been abandoned, in favor of a more perfect emulation of the humility and service shown by Christ and the apostles. We more clearly perceive that the victory of the Church is to be over sin, the devil, and death, not against our fellow men and their churches.

The words of St. John hold good about sins against unity:If we say we have not sinned, we make him a liar, and his word is not in us.So we humbly beg pardon of God and of our separated brethren, just as we forgive them that trespass against us. (UR, 7)

The Council acknowledges that Catholics are capable of all types of sin, including sins against unity. Such sins are found not only in the aforementioned historical events where Catholics helped occasion schism by undue severity or giving scandal, but also in a general posture of hostility or bigotry toward other Christians, without giving due weight to their human dignity and status as baptized brethren in Christ. Any authentic spiritual renewal must begin with an acknowledgement of sin, followed by repentance.

Moving to more concrete actions, the Council says:

In certain special circumstances, such as the prescribed prayersfor unity,and during ecumenical gatherings, it is allowable, indeed desirable that Catholics should join in prayer with their separated brethren. Such prayers in common are certainly an effective means of obtaining the grace of unity, and they are a true expression of the ties which still bind Catholics to their separated brethren.For where two or three are gathered together in my name, there am I in the midst of them.(UR, 8)

The Council confines common prayer to special circumstances oriented toward Christian unity, as opposed to having Catholics participate in Protestant prayer meetings, for the latter have a sectarian character. Nonetheless, common prayer in an ecumenical context is positively encouraged, since this certainly

can obtain the grace of unity. Most notably, the Council applies the words of Matthew 18:20, a verse traditionally applied to the Church, to the bond between Catholic and non-Catholic. In this way, the Council plainly acknowledges that separated Christians are still bound to the Church, and Christ is among them by virtue of that bond.

Yet worship in common (communicatio in sacris) is not to be considered as a means to be used indiscriminately for the restoration of Christian unity. There are two main principles governing the practice of such common worship: first, the bearing witness to the unity of the Church, and second, the sharing in the means of grace. Witness to the unity of the Church very generally forbids common worship to Christians, but the grace to be had from it sometimes commends this practice. The course to be adopted, with due regard to all the circumstances of time, place, and persons, is to be decided by local episcopal authority, unless otherwise provided for by the Bishops’ Conference according to its statutes, or by the Holy See. (UR, 8)

Worship in common is not an end in itself, nor is it oriented toward the merely human concerns of making friendly relations and being inoffensive to others. It is subordinate to the aim of restoring Christian unity, and thus should only be used when it helps and does not hinder this aim. Note the Council says that, in general, bearing witness to the Church’s unity forbids common worship to Christians.

The Council would not say this if it conceived of the Church

as some composite of all the various Christian denominations. Rather, the Council considers the Church

to already possess full unity in the Catholic Church, and so common worship with other Christians would generally serve to deny the Church’s real, visible unity, by giving the impression that Catholic unity is deficient. Still, common worship may be commendable in certain instances due to the sharing in the means of grace. By such common worship, separated Christians may share in the graces of the Church, including that of unity, albeit imperfectly. This ecumenical worship is motivated by the desire to serve and minister even to separated Christians, sharing whatever graces of the Church they are equipped to receive.

Catholics, who already have a proper grounding, need to acquire a more adequate understanding of the respective doctrines of our separated brethren, their history, their spiritual and liturgical life, their religious psychology and general background. Most valuable for this purpose are meetings of the two sides—especially for discussion of theological problems—where each can treat with the other on an equal footing—provided that those who take part in them are truly competent and have the approval of the bishops. From such dialogue will emerge still more clearly what the situation of the Catholic Church really is. In this way too the outlook of our separated brethren will be better understood, and our own belief more aptly explained. (UR, 9)

Studying other Christian traditions is encouraged only for well-formed Catholics, for whom there is no danger to faith, for the purpose of engaging non-Catholics in discussion. This is consistent with traditional practice. What is new here is the recommendation that ecumenical dialogue should be on an equal footing.

This is not to deny the objective superiority of the Catholic Church’s ecclesiastical status or the truth of her doctrine. Rather, it is a call to engage others on the basis of their equal human dignity. This requires Catholics to perform a humble self-emptying, setting aside their rightful prerogatives in order to serve the good of their brethren.

Understanding the perspectives of non-Catholic Christians is not an end in itself, but is a necessary condition for conveying the true situation and belief of the Catholic Church to them. Without such understanding, Catholics will find themselves talking past the other party, as the conventional formulations of belief might not address the concerns specific to a denominational tradition.

Sacred theology and other branches of knowledge, especially of an historical nature, must be taught with due regard for the ecumenical point of view, so that they may correspond more exactly with the facts.

(UR, 10) This ecumenizing of theology and ecclesiastical history does not entail falsification for the sake of diplomacy. Rather, these studies should take into account the perspectives of other Christians when making evaluations. The moral status of an act cannot be separated from intent, and the only way we can grasp the intent of other Christians is to learn something of their psychology, their cultural history, and their spiritual traditions. In this way, we may more accurately and fairly assess their condition with respect to the Catholic Church.

All future pastors and priests are expected to master a theology that has been carefully worked out in this way and not polemically…

(UR, 10) This recommendation is not a call to change the content of Catholic theology, but to alter its tone and to include more accurate representation of the perspectives of other Christians. Ecumenically informed theology does not set out to prove argumentatively that Catholics are right and others are in error, this being presupposed by the act of accepting the Catholic faith in its integrity. Rather, it recognizes that not all error is culpable, and that there is much of the true Christian faith to be found outside the visible Catholic Church. The Catholic Church must embrace all that is authentically Christian, since all the gifts of the New Covenant are entrusted to her.

The way and method in which the Catholic faith is expressed should never become an obstacle to dialogue with our brethren. It is, of course, essential that the doctrine should be clearly presented in its entirety. Nothing is so foreign to the spirit of ecumenism as a false irenicism, in which the purity of Catholic doctrine suffers loss and its genuine and certain meaning is clouded. (UR, 11)

The method of expressing Catholic theology is to be changed in a way so that dialogue with separated Christians is not needlessly impeded. Yet at the same time the doctrine should be clearly presented in its entirety.

There is no hint that any doctrine of the Church should be hidden or obscured from the view of non-Catholics. On the contrary, the purpose of reforming theological expressions is to make them more clearly understood to those who conceptualize the faith in different terms. For example, after the Council of Ephesus, John of Antioch was reconciled to the Church by a formula of union using terms distinct from the Ephesian doctrine he had misconstrued. The purpose of ecumenism is to bring all Christians to the one faith, so we must try to overcome verbal and conceptual obstacles to assenting to the faith.

The Council derides false irenicism,

where we try to cloud the meaning of Catholic doctrine or subtract from its contents, as being absolutely foreign to the spirit of ecumenism. Since the whole point of ecumenism is to remove needless obstacles to unity in faith, its purpose is defeated if Catholic doctrine is misrepresented. In that case, we are worse off than when we started, for the other Christians are denied even the opportunity to know what the Catholic doctrine is, much less come to a better understanding of it.

In the post-Conciliar era, we have seen too much of false ecumenical theology, which has become practically synonymous with fuzzy thinking and obscuring traditional Catholic dogma. The Council, on the contrary, instead of prescribing vagueness, says, the Catholic faith must be explained more profoundly and precisely, in such a way and in such terms as our separated brethren can also really understand.

(UR, 11) Note the term ‘also’; the intent is to make Catholic dogma as intelligible to other Christians as it already is to Catholics. Instead of making Catholic dogma intelligible to other Christians, however, many modern theologians have succeeded only in making it unintelligible to Catholics.

The Council suggests that ecumenical dialogue may be aided by keeping this in mind: When comparing doctrines with one another, they should remember that in Catholic doctrine there exists a ‘hierarchy’ of truths, since they vary in their relation to the fundamental Christian faith.

(UR, 11) The concern here, as always, is to facilitate dialogue, not to suppress it. For example, if Protestants object to a Marian doctrine of the Church as being non-Biblical or extraneous to the faith, the response is not to exclude that doctrine from discussion, but to show how that doctrine is hierarchically linked to more central doctrines, e.g., the Incarnation. In this way, other Christians can better appreciate the organic structure of Catholic doctrine, so that what may seem arbitrary or extraneous is better understood in connection with the central mysteries of faith.

It is not admissible for a Catholic to interpret the hierarchy

of truths to mean that some doctrines are disposable or inessential to the faith. To participate in the fullness of Catholic unity, it is necessary to accept the faith whole and entire. To deny the Immaculate Conception, for example, creates defects in one’s faith in the Incarnation, original sin, and the Redemption. It also requires a denial of papal infallibility, which in turn requires a denial of the ecumenical council that defined it. All the doctrines are linked in an organic unity, so a denial of one detracts from one’s faith in the whole. With good reason, then, Cardinal Schönborn says:

Thehierarchy of truthdoes not meana principle of subtraction,as if faith could be reduced to someessentialswhereas therestis left free or even dismissed as not significant. Thehierarchy of truth… is a principle of organic structure. It should not be confused with the degrees of certainty; it simply means that the different truths of faith areorganizedaround a center… (Introduction to the Catechism of the Catholic Church, p. 42.)

Cardinal Schönborn’s reference to degrees of certainty

alludes to the traditional distinctions (expressed for example in Ludwig Ott’s Fundamentals of Catholic Dogma) in the level of certainty with which a doctrine has been defined. These distinctions depend not on the organic centrality of the doctrine, but on the level of authority or definitiveness with which the Church has pronounced on the question. These degrees of certainty are, in descending order: de fide, fides ecclesiastica, sententia fidei proxima, sententia ad fidem pertinens, sententia communis, sententia probabilis, etc. All of the familiar required Catholic doctrines are de fide, so there is no question of the hierarchy of truth

expressing any variation in certainty. All de fide dogmas, as well as those doctrines that are fides ecclesiastica (defined by the extraordinary magisterium, but not of divine revelation; e.g., dogmatic facts), are infallibly certain.

In these days when cooperation in social matters is so widespread, all men without exception are called to work together, with much greater reason all those who believe in God, but most of all, all Christians in that they bear the name of Christ. Cooperation among Christians vividly expresses the relationship which in fact already unites them, and it sets in clearer relief the features of Christ the Servant. (UR, 12)

Christians have a special calling to cooperate in social matters, to show that they all serve in the name of the same Christ. Possible domains of cooperation include:

…a just evaluation of the dignity of the human person, the establishment of the blessings of peace, the application of Gospel principles to social life, the advancement of the arts and sciences in a truly Christian spirit… the use of various remedies to relieve the afflictions of our times such as famine and natural disasters, illiteracy and poverty, housing shortage and the unequal distribution of wealth. (UR, 12)

There are two aspects of Christian social activity listed here: (1) activities which apply specifically Christian principles to the public sphere, and (2) corporal works of mercy. The latter, no less than the former, are required by Christian duty. Catholics, or Christians more generally, may disagree as to the most effective or moral means of addressing social problems, but they are not permitted to ignore them as something extraneous to their religious duty.

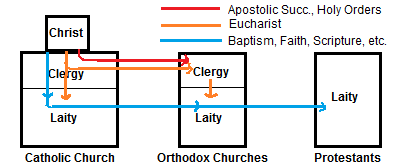

The Council now turns to addressing relations with specific classes of separated Christians, distinguishing two main types of division. First are the divisions of the East, when several churches rejected the Councils of Ephesus and Chalcedon, and the Eastern patriarchates split from Rome. The second set of divisions consists of those occasioned by the Reformation. In this latter group, the Council singles out the Anglican Communion as a communion where Catholic traditions and institutions in part continue to exist.

(UR, 13)

The basis of division is not so much between heresy and schism—for there is heresy among the Churches that rejected Ephesus—but rather between separated bodies that remain organized as particular Churches, and those that are not. Thus the Council repeatedly refers to the Eastern bodies as Churches, but does not do likewise for the post-Reformation groups. The latter, by contrast, are described vaguely as Churches and ecclesial communities,

or as Communions.

It is never once indicated that any of these bodies might be a duly constituted particular or local Church. Even the most Catholic

of these communities, that of the Anglicans, is characterized solely as a Communion. The reason for this distinction is that virtually none of the Western groups (save the Old Catholics and related sects) have a valid Eucharist or validly ordained clergy. Thus the divisions with Western Christians are in some ways more profound, since they depend not only on questions of theology and discipline, but also on differing basic notions of the Church.

For many centuries the Church of the East and that of the West each followed their separate ways though linked in a brotherly union of faith and sacramental life; the Roman See by common consent acted as guide when disagreements arose between them over matters of faith or discipline. (UR, 14)

The Church of the East

and of the West

refers to the Eastern patriarchates and the Latin Church respectively. The Roman See is here depicted as an arbiter of disputes among the various particular Churches, East and West. This is consistent with the Council’s emphasis on the Pope’s role as universal pastor, rather than as Latin patriarch.

…it is a pleasure for this Council to remind everyone that there flourish in the East many particular or local Churches, among which the Patriarchal Churches hold first place… (UR, 14)

This is a reminder, not a new teaching. The Eastern Churches are particular or local Churches in the sense that there is nothing wanting in their internal constitution. However, since they lack communion with Rome, they are not members of the universal Church, which is an essential characteristic of a particular Church. Thus their status as particular Churches is defective or wounded,

to use Pope Benedict’s term.

Hence a matter of primary concern and care among the Easterns, in their local churches, has been, and still is, to preserve the family ties of common faith and charity which ought to exist between sister Churches. (UR, 14)

Here we are speaking of ties among the Easterns, so the expression sister Churches

is applied only to the Easterns in relation to each other. Strictly speaking, the Latin Church may also be considered a sister Church,

but it would be an error to regard the Catholic Church as such. In fact, the Council later says, We thank God that many Eastern children of the Catholic Church, who preserve this heritage, and wish to express it more faithfully and completely in their lives, are already living in full communion with their brethren who follow the tradition of the West.

(UR, 17) The particular Churches and their faithful are all children of the Catholic Church. Those who follow Eastern traditions are the brethren of those who follow the Western tradition, and all are children of the Catholic Church, with which they should aspire to live in full communion.

Upholding the established principle that no burden beyond what is essential

should be imposed, the Council desires that:

…every effort should be made toward the gradual realization of this unity, especially by prayer, and by fraternal dialogue on points of doctrine and the more pressing pastoral problems of our time. Similarly, the Council commends to the shepherds and faithful of the Catholic Church to develop closer relations with those who are no longer living in the East but are far from home… (UR, 18)

Only vague prescriptions are given for ecumenical relations with the Orthodox, since this decree is just a presentation of the Council’s general outlook on ecumenism, not a policy paper.

…the Council hopes that the barrier dividing the Eastern Church and Western Church will be removed, and that at last there may be but the one dwelling, firmly established on Christ Jesus, the cornerstone, who will make both one. (UR, 18)

Here the barrier is that between particular Churches of the East and of the West (i.e., the Latin Church). The expressed desire for this reunion does not entail a denial that the Catholic Church (including all Rites) has universal jurisdiction and the fullness of unity already. This has already been asserted by the Council in Lumen Gentium, for example. Earlier popes and councils expressed a similar desire for reunion, without denying traditional Catholic belief about the universal Church.

The Council now turns to the separated Churches and ecclesial Communities

of the West, which began to split from the Apostolic See from the late Middle Ages onward. The decree never specifies which sects are Churches and which are Communities, yet we may apply the notion of a particular Church, used in Lumen Gentium and Orientalium Ecclesiarum, to make such a distinction. A particular Church has a valid episcopate and Eucharist, whereby it possesses a constitution analogous to that of the Catholic Church as a whole. Accordingly, the Orthodox communities of the East were called Churches, since they retain the constitution of particular Churches.

If we follow the decree’s starting point of toward the end of the Middle Ages,

we find that several early schismatic groups retained the constitution of Churches. Notable among these are the Avignon papacy, the Pisan conciliarists, and the Hussites. These were all eventually reconciled to the Catholic Church, except for a Hussite remnant that became the Moravian Church. During the early Reformation, most dissenters at first sought to preserve something of the hierarchical structure of the Catholic Church. To this day, the Anglicans and Lutherans claim to have a valid episcopate in historic succession from the Apostles.

However, Pope Leo XIII confirmed in Apostolicae Curae (1896) that Anglican orders are invalid, due to defects in intent and form resulting from a denial of the sacerdotal power of the priesthood. This judgment has been accepted by all subsequent pontiffs, and so Anglican priests converting to Catholicism need to be re-ordained. Thus the Anglican Communion is not a true particular Church, and by extension, neither are the Lutherans, who are even further from the Catholic understanding of priesthood.

Nonetheless, the fact that Anglican priests are admitted directly to Holy Orders, even being dispensed from the law of celibacy, implies that the Church recognizes something more than ordinary laymen in the Anglican priesthood. Thus the Anglican Communion might be called a Church, but only in an equivocal or improper sense, referring to an intention rather than a sacramental reality. In other words, the Anglicans have tried to constitute themselves as a particular Church, but are unsuccessful due to their lack of a valid episcopate. This is in contrast with other Protestant groups, which do not even attempt or desire to constitute themselves according to the Catholic understanding of a Church.

Among the extant Christian sects of the West, only the Old Catholics (who deny papal infallibility) and related groups have a valid episcopate and Eucharist, and thus may be called particular Churches. The Anglicans, and to a lesser degree the Lutherans and Moravians, might also be called Churches, but only in the highly equivocal sense discussed above. This leaves the vast mass of the rest of Protestantism, which is composed only of ecclesial Communities.

These differ not only from the Church’s constitution, but even from each other in fundamental points of ecclesiology, discipline, and doctrine. Accordingly, the Council makes no attempt to describe them in the decree.

The Council recognizes that, among the diverse sects, not all are agreed that ecumenism is even a desirable endeavor. Further, in these Churches and ecclesial Communities there exist important differences from the Catholic Church, not only of an historical, sociological, psychological and cultural character, but especially in the interpretation of revealed truth.

(UR, 19) Nonetheless, the Council hopes to facilitate and encourage ecumenical dialogue by setting forth some considerations.

The Council first appeals to those Christians who confess faith in Jesus Christ as God and Lord and as the sole Mediator between God and men, to the glory of the one God, Father, Son and Holy Spirit.

(UR, 20) Although they may differ from the Church even on weighty doctrines of Christology and soteriology, the Council rejoices that they look to Christ as the source and center of Church unity.

Since Christ is in reality the source of the Church’s unity, any genuine desire for union with Christ will necessarily impel Christians toward greater unity with each other, in keeping with Christ’s will.

The Protestants’ love and devotion to the Holy Scriptures, especially the Gospel, which is the power of God for salvation to every one who has faith,

is another important basis of unity. Since most of the substance of Holy Scripture is common to all denominations, this provides a shared starting point for dialogue. Still, the Council realizes there are important differences on how to interpret Scripture: For, according to Catholic belief, the authentic teaching authority of the Church has a special place in the interpretation and preaching of the written word of God.

(UR, 21)

Whenever the Sacrament of Baptism is duly administered as Our Lord instituted it, and is received with the right dispositions, a person is truly incorporated into the crucified and glorified Christ, and reborn to a sharing of the divine life… (UR, 22)

Now, for the first time, the Council describes what sort of imperfect communion with the Church is attained by separated Christians through baptism. When administered with the proper form and intent, baptism truly incorporates a person into Christ. Baptism therefore establishes a sacramental bond of unity which links all who have been reborn by it.

In this sense, all the baptized are united to the Church.

But of itself Baptism is only a beginning, an inauguration wholly directed toward the fullness of life in Christ. Baptism, therefore, envisages a complete profession of faith, complete incorporation in the system of salvation such as Christ willed it to be, and finally complete ingrafting in eucharistic communion.(UR, 22)

Since baptism is a sacrament of initiation into the life of faith, one may only reap its full benefits if one persists in faithful participation in the system of salvation, administered sacramentally by the Church. Thus, the Protestants lack the fullness of unity with us flowing from Baptism…

They do not fully benefit from baptism because it is not followed by profession of the full Catholic faith and participation in the sacramental system of salvation instituted by Christ. Still, they receive the principal, immediate effects of baptism: the remission of original sin and prior personal sin, as well as incorporation into the body of Christ.

The body of Christ is the Church, so all the baptized are in the Church, even though not all are of the Church. That is to say, some may be in positions of rebellion or estrangement toward the Church, much as members of a nation may be outlaws or emigrants, but do not cease to be nationals. Those who apostatize or persist in unrepentant sin do not undo

their baptism in this life, but fail to benefit from it as they oppose Christ in their will. They are only bodily present in the Church. Yet those who, in good faith, are estranged from the hierarchical Church and ignorant of their duties, might receive some benefit from baptism followed by a life of faith, though do not receive the full benefit of baptism, which is full unity in Christ’s Church.

In Scholastic tradition, it was said that sacraments administered by the excommunicated were valid and efficacious, but did not confer grace, except by Baptism in case of necessity. By grace

was meant the sanctifying grace of salvation entrusted to the Church alone. This withholding of grace was due to the sin of receiving a sacrament against the Church’s prohibition. Yet for the sacrament to be efficacious at all, it must impart some sort of grace. The Council acknowledges this, saying that separated Christians are strengthened by the grace of Baptism.

(UR, 23) This does not mean that they thereby receive grace that effects salvation, for their deficiency of unity (in obedience or in faith) remains. However, this same Council also recognizes that this state of imperfect communion is often inculpable, and thus ought not to be reckoned as a sin against unity. Those who are born into separated communities do not necessarily bear the culpability of one who receives sacraments from a willful excommunicate. They are often not aware of any disobedience to Christ’s Church.

With similar charity, the Council affirms on the one hand that the ecclesial Communities have not retained the proper reality of the eucharistic mystery in its fullness,

yet nevertheless when they commemorate His death and resurrection in the Lord’s Supper, they profess that it signifies life in communion with Christ and look forward to His coming in glory.

(UR, 22) Even when we are dealing with an invalid eucharist, which has no sacramental efficacy, separated Christians may thereby participate in an imperfect action toward ecclesial unity, impelled by their desire for communion with Christ now and at the end of time.

The Council does not propose that the separated communities should content themselves with what unifying graces they have. Rather, the teaching concerning the Lord’s Supper, the other sacraments, worship, the ministry of the Church, must be the subject of the dialogue.

(UR, 22) The goal of ecumenism is to perfect the unity of the Church, so the points of disagreement are not to be swept aside, but on the contrary are precisely the issues that need to be worked out.

This Sacred Council exhorts the faithful to refrain from superficiality and imprudent zeal, which can hinder real progress toward unity. Their ecumenical action must be fully and sincerely Catholic, that is to say, faithful to the truth which we have received from the apostles and Fathers of the Church, in harmony with the faith which the Catholic Church has always professed, and at the same time directed toward that fullness to which Our Lord wills His Body to grow in the course of time. (UR, 24)

Real ecumenism does not mean whitewashing over our differences in order to proclaim a superficial unity. Such premature shortcuts only hinder real unity, since it is based on deceiving the other party as to the real Catholic position. We have seen in the post-Conciliar era many such ill-conceived attempts, which have done nothing to create Christian unity, but on the contrary have occasioned disunity within the visible Catholic Church, as doubts arise as to what the real Catholic teaching is. True ecumenism, according to the Second Vatican Council, requires fidelity to the teaching of the Apostles and the Fathers, the faith which the Catholic Church has always professed.

Any attempt to change or disguise traditional Catholic doctrine will only ring false to other Christian groups. It will only prove to them that the Catholics are inconstant in their teaching, and thus the Catholic Church does not preserve the fullness of faith. Worse, it will re-open among Catholics questions long settled by definitive teachings, so that younger generations are also separated from the perennial teachings of the Church, and are little better off than Protestants.

Already we see many liberal

Catholics who would remake the Church into a big tent

left-center political party, as if the Church’s catholicity was measured by an embrace of all doctrines. This is not Catholicism, but a Protestantism so homogenized that most devout Protestants would reject it, being faithful to their particular traditions. The evangelicals are especially resistant to such diluting of doctrine, as they find the constant testimony of Scripture opposed to such false irenicism.

From the prophets railing against the sins of Israel and its kings, to Christ’s stern rebuke of the Pharisees and priests, we see that divine revelation is not something to be subjected to diplomatic compromise. Although we have a duty to treat our brethren with charity and respect, our first allegiance is to God, not to the whims and desires of the world. The progressive

program of today is the embarrassing folly of tomorrow. The Church therefore does not tie her destiny to any of the cultural fads of the moment, but only to the divine mission permanently entrusted to her. It is her duty to offer the saving Gospel not only to her own members, but to those outside her visible structure, and indeed to the whole world. This evangelical mission is at the heart of ecumenism, as men are to be saved not merely as individuals, but as one community united in Christ.

© 2012 Daniel J. Castellano. All rights reserved. http://www.arcaneknowledge.org

| Home | Top |