Overview

Chapter I: The Mystery of the Church

1.1 "Subsistit in"

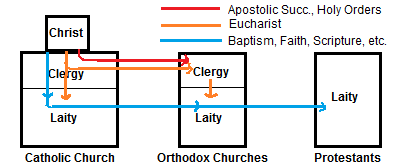

1.2 "Elements of Sanctification"

Chapter II: On the People of God

2.1 Members of the Church

2.2 The Church in Relation to Other Christians

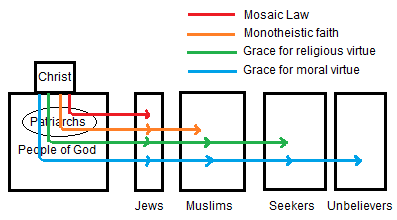

2.3 The Church in Relation to Non-Christians

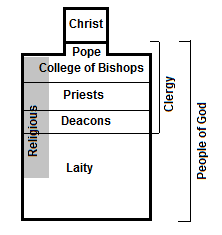

Chapter III: On the Hierarchical Structure of the Church

3.1 The College of Bishops

3.2 Papal Infallibility

3.3 Local Ministry of Bishops, Priests and Deacons

Chapter IV: The Laity

Chapter V: The Universal Call to Holiness in the Church

Chapter VI: Religious

Chapter VII: The Eschatological Nature of the Church

Chapter VIII: The Blessed Virgin Mary in the Mystery of Christ and the Church

Conclusion: Ecclesiology of Lumen Gentium

Having dealt with the pressing matter of liturgical reform in Sacrosanctum Concilium, the Second Vatican Council’s next great effort was to define the Church in relation to the modern world. This required a formulation of ecclesiology that more clearly articulated the role of the laity, while at the same time explaining the hierarchical constitution of the Church in terms that are both intelligible to modern man and consonant with the original Christian mission. It is in this dogmatic constitution on the Church that ressourcement theology made its first lasting mark on the Council. Setting aside conventional juridical definitions, this document, titled Lumen Gentium, embarks on a discussion of how the hierarchical Church serves the divine mission proposed by her Founder, and how her members contribute to the realization of the kingdom of God. Every exercise of authority is subordinate to the call to holiness, and when this is realized, even modern democratic man can recognize the good of such authority. The document makes extensive use of Patristic and Biblical sources, consistent with the approach of ressourcement, yet at the same time, it holds true to the ecclesiology upheld at Trent and Vatican I.

When examined closely, Lumen Gentium’s ecclesiology is remarkably traditional, as contrasted with some of the more radical formulations proposed by ressourcement theologians and by some modern interpreters of the Council. This is not to say that there is nothing new in the document; quite the contrary, the constitution is an invaluable advancement in the discussion of how the Church should conceive of herself with respect to the rest of the world. Lumen Gentium is the key to understanding much of the Council’s subsequent work, including the Decree on the Churches of the Eastern Rite (Orientalium Ecclesiarum) and the decree on ecumenism (Unitatis Redintegratio), promulgated on the same day (November 21, 1964), as well as the later declaration on the relation to non-Christian religions (Nostra Aetate). It is only when the Church more fully articulates her own mission and constitution that she can define her relation to the rest of the world.

Although this document is a “dogmatic constitution on the Church,” there is little if any new dogma defined here. As with most of the Council’s work, the primary intention was not to define new doctrine, but to articulate existing doctrine in a way that makes possible a pastoral engagement with the world in modern terms. Given the near unanimity of its approval (2,151 to 5 votes), it is hardly sustainable that there could be anything contrary to the faith in this document, rightly construed. If Lumen Gentium was an attempt to redefine or alter the Church’s constitution, it would never have passed muster among the hundreds of staunchly traditionalist bishops, nor among the orthodox majority. Yet the best proof of its orthodoxy is an examination of the document itself.

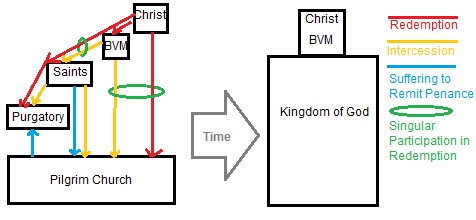

This document is also notable for containing one of two possible instances (the other is in Dei Verbum) where the Council appears to have defined a doctrine at least incidentally. In the discussion of the role of the Blessed Virgin, we find, for the first time in an ecumenical Council, an acknowledgement of the legitimacy of the title Mediatrix. However, the Council does not define exactly what is meant by this title, except to affirm that this does not diminish the unique mediation of Christ. The mere mention of the Blessed Virgin as Mediatrix is a remnant of the pre-conciliar desire by some bishops to define this doctrine formally. The project was abandoned for fear of creating a further stumbling-block for reconciliation with the Protestants, yet the “progressives” did not succeed in suppressing this discussion altogether. In fact, Lumen Gentium assigns an entire section to the discussion of the Blessed Virgin’s importance to the life of the Church.

Lumen Gentium represents an important synthesis of Biblical, Patristic, medieval and Tridentine ecclesiology, combined with orthodox elements of the new theological movement. Understanding Lumen Gentium is essential to the interpretation of the Council’s subsequent documents, especially Unitatis Redintegratio. It is critical to take the document in its entirety, rather than to select some sections over others. For example, we cannot accept what the Council says about “the people of God” without also accepting its explanation of the hierarchy and the laity. Similarly, we cannot conceive of the Church’s mission to the world without reference to her divine commission and her mystical character as the body of Christ. Those who cite Lumen Gentium as evidence of a brand new ecclesiology do so by quoting it partially or non-contextually. In this commentary, we will strive to make clear what is the traditional basis for the constitution’s assertions, following the document’s own citations.

Christ is the “light of nations” (lumen gentium), and the Church is entrusted to bring this light into the world. As such, the Church is a sign both of union with God and of the unity of the human race. For this reason, it is her responsibility to explain her “inner nature and universal mission” so that it is understandable to the nations. The Council takes up this task “following faithfully the teaching of previous councils.” (LG, 1)

God the Father created the world “by a free and hidden plan of his own wisdom and goodness”—that is, not out of necessity. “His plan was to raise men to a participation in the divine life.” Following Biblical and Patristic teaching (Romans 8; SS. Cyprian, Hilary, Cyril, Augustine, Gregory, John Damascene), the Council affirms that God foreknew and predestined from eternity that the elect should be conformed to the image of His Son, the firstborn among many brethren. “He planned to assemble in the holy Church all those who would believe in Christ.” The Church was foreshadowed from the beginning of the world, prepared in the covenant with Israel, made manifest in the Christian era, and will achieve completion at the end of time, when all the just, from Adam to the last of the elect, are “gathered together with the Father in the universal Church.” (LG, 2)

It is in the Son that God the Father predestined the elect to become adopted sons. In obedience to the Father, “Christ inaugurated the Kingdom of heaven on earth and revealed to us the mystery of that kingdom,” and this obedience redeemed the world. “The Church, or, in other words, the kingdom of Christ now present in mystery, grows visibly through the power of God in the world.” The work of redemption is carried on through the eucharistic sacrifice, which draws men to Christ and brings about the unity of believers as the body of Christ. “All men are called to this union with Christ, who is the light of the world…” (LG, 3)

The Holy Spirit was sent on Pentecost to sanctify the Church continually. He acts as the advocate of the faithful and testifies to their status as adopted sons. The Spirit guides the Church in truth and equips her with “hierarchical and charismatic gifts.” (LG, 4)

The mission of the Church is “to proclaim and to spread among all peoples the Kingdom of Christ and of God and to be, on earth, the initial budding forth of that kingdom.” (LG, 5)

Invoking various New Testament images of the Church, we find that the Church is a sheepfold whose shepherd is Christ, and he is also the door. (Shepherds would lie down and serve as the door to the pen.) The Church is also like a cultivated olive tree whose roots are the prophets, and her members are like the branches of the true vine that is Christ. The Church is also compared to a building, whose cornerstone is Christ, upon which the Church is built by the apostles. It is the place where God dwells among men, a Temple symbolized by our houses of worship, but really built of us as living stones. The Church is also “our mother” and the “spotless spouse of the spotless Lamb,” subject to Christ in love and fidelity. On earth, the Church is in exile, seeking those things above, where Christ is seated at the right hand of the Father, until her hidden life appears in glory with her Spouse. (LG, 6)

In the human nature united to Himself the Son of God, by overcoming death through His own death and resurrection, redeemed man and re-molded him into a new creation. By communicating His Spirit, Christ made His brothers, called together from all nations, mystically the components of His own Body. (LG, 7)

In the Body of Christ, which is the Church, “the life of Christ is poured into the believers who, through the sacraments, are united in a hidden and real way to Christ.” (cf. St. Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theol. III, q. 62, a. 5, ad 1) We are formed in the likeness of Christ through baptism. “Really partaking of the body of the Lord in the breaking of the eucharistic bread, we are taken up into communion with Him and with one another.”

Different members of the Body have different functions, for which the Spirit assigns various gifts. “What has a special place among these gifts is the grace of the apostles to whose authority the Spirit Himself subjected even those who were endowed with charisms.” The Spirit gives the Body unity and encourages love among its members, so that all rejoice and suffer together.

Christ “is the head of the Body which is the Church.” All members ought to be molded in his likeness.

For this reason we, who have been made to conform with Him, who have died with Him and risen with Him, are taken up into the mysteries of His life, until we will reign together with Him. On earth, still as pilgrims in a strange land, tracing in trial and in oppression the paths He trod, we are made one with His sufferings like the body is one with the Head, suffering with Him, that with Him we may be glorified. (LG, 7)

Christ has shared with us his Spirit, one and the same in the Head and in the Body, so that Body is unified with life. The work of the Spirit in the Church is analogous of that of the principle of life or soul in the human body. (cf. Tertullian, Against Marcion 3, 7) Christ loves the Church as his bride, much as a man loves his wife as his own body.

Christ, the one Mediator, established and continually sustains here on earth His holy Church, the community of faith, hope and charity, as an entity with visible delineation through which He communicated truth and grace to all. But, the society structured with hierarchical organs and the Mystical Body of Christ, are not to be considered as two realities, nor are the visible assembly and the spiritual community, nor the earthly Church and the Church enriched with heavenly things; rather they form one complex reality which coalesces from a divine and a human element. (LG, 8) [Emphasis added]

Here the Council sets forth clearly its teaching that the visible hierarchical Church is not something distinct from the Mystical Body of Christ that has been discussed, but rather they are one and the same thing. Though the Church is composed of human members, the faithful are formed according to Christ in baptism and really united in His Body through eucharistic communion. The Holy Spirit unifies the Body in the life of Christ, so that the same Spirit and the same life dwells in the Head and the Body. True to its foundation in God Incarnate, the Church is a union of divine and human elements. “As the assumed nature inseparably united to Him, serves the divine Word as a living organ of salvation, so, in a similar way, does the visible social structure of the Church serve the Spirit of Christ, who vivifies it, in the building up of the body.” The visible social structure of the Church is her human element, in analogy with Christ’s human nature, and this structure is vivified by the Spirit of Christ, building up the Body, much as the Word dwelling in the assumed human nature made the latter an agent of salvation.

This is the one Church of Christ which in the Creed is professed as one, holy, catholic and apostolic which our Saviour, after His Resurrection, commissioned Peter to shepherd, and him and the other apostles to extend and direct with authority, which He erected for all ages as “the pillar and mainstay of the truth.” (LG, 8)

The one Church of Christ is that union of human and divine elements just discussed. The Church is both a visible assembly and a spiritual community, both earthly and heavenly. Her human or earthbound aspect, i.e., her social structure, serves and is animated by the Spirit of Christ, and acts as an organ of salvation by bringing the sacraments to the world. This structure is grounded in the commission that Christ imparted to Peter and the other apostles, endowing them with an authority that would last through the ages.

This Church constituted and organized in the world as a society, subsists in the Catholic Church, which is governed by the successor of Peter and by the Bishops in communion with him, although many elements of sanctification and of truth are found outside of its visible structure. (LG, 8)

In continuity with the previous sentence, which mentioned Christ’s commissioning of Peter and the apostles to direct the Church with authority, the Council now elaborates that this Church is now “governed by the successor of Peter and by the Bishops in communion with him.” Clearly, the Catholic Church is the same as that established under the authority of Peter, since it is governed by his successor, and we were just told that Christ erected the Church under apostolic authority “for all ages.” Moreover, it was clearly stated just previously that the hierarchical Church is not to be considered a distinct reality from the Mystical Body of Christ.

In view of these identities, it is strange that the document says that the Church of the Creed “subsists in” the Catholic Church, rather than simply saying that the Church of the Creed is the Catholic Church. This softened language appears to be motivated by the desire to recognize that there are “many elements of sanctification and of truth” outside its visible structure. In other words, the Church of Christ might in some sense extend beyond the visible structure of the Catholic Church.

This subtle distinction can easily be misread, and indeed has been misread far more frequently than it has been correctly interpreted. The Council definitely did not intend to say that the Church of Christ is a distinct entity from the visible, hierarchical Catholic Church. It plainly rejected that idea just a few sentences earlier. Any authentic, honest attempt to discern the Council’s meaning must harmonize with its earlier declarations that the hierarchical Church and the heavenly Church are not distinct realities, and that the Church of the Creed was erected under the authority of Peter and the apostles, to last for all ages.

Fortunately, we do not have to guess at the Council’s meaning, for the matter has been clarified by official magisterial pronouncements by the Popes, starting with Pope Paul VI. Just months before Lumen Gentium was ratified, the pontiff issued his encyclical Ecclesiam Suam, which approvingly quotes Pope Pius XII in Mystici Corporis: “The doctrine of the Mystical Body of Christ, which is the Church, a doctrine revealed originally from the lips of the Redeemer Himself…” Here the equation of the Church with the Mystical Body of Christ is plainly pronounced as de fide. Lest there should be any doubt that Lumen Gentium did not intend to break continuity with this tradition, the same Pope announced, when promulgating the Constitution, “There is no better comment to make than to say that this promulgation really changes nothing of the traditional doctrine. What Christ willed, we also will. What was, still is. What the Church has taught down through the centuries, we also teach.” In later years, Pope Paul would become exasperated with attempts to interpret the Council as overturning previous dogma. That this was not the case was obvious to him, since he had worked tirelessly to ensure that no dogmatic controversies were to be taken up by the Council, but rather it was to focus on pastoral aims. The near unanimous approval of the document would have been impossible if the Fathers had understood it to contradict the perennial doctrine expressed in Mystici Corporis.

Still, some account needs to be made of the choice of wording. According to tapes of the Council, the phrase subsistit in was proposed by none other than Sebastian Tromp, a Thomist traditionalist who had been instrumental in authoring Mystici Corporis. He says:

Possumus dicere: itaque subsistit in Ecclesia catholica, et hoc est exclusivum, in quantum dicitur: alibi non sunt nisi elementa. Explicatur in textu. [Emphasis by speaker.]

We can say: ‘and so it subsists in the Catholic Church,’ and this is exclusive, inasmuch it is said, elsewhere there are not but elements. It is explained in the text.

Tromp understood this wording to have an exclusive meaning, so that the Church of Christ subsists in the Catholic Church and nowhere else. Elsewhere there are only “elements” of sanctification, as we shall discuss later. Given that Tromp had helped author Mystici Corporis and had helped arch-traditionalist Cardinal Ottaviani prepare the original schemata that were set aside by the Council, it is hardly surprising that subsistit in should be given a perfectly traditional interpretation in its origin. The word subsistit was to replace the ambiguous adest (“is present”) in order to signify specifically that the Church of Christ is present in the Catholic Church and nowhere else. Tromp was an accomplished Latinist, and knew that subsistere originally meant “to remain standing,” and by the Middle Ages it was practically synonymous with “to exist.” That is to say, the Church of Christ remained in the Catholic Church, even as many members broke away. This is why Tromp understood subsistit to have an exclusive meaning, more so than adest or est.

Still, many liberal Catholics and non-Catholics interpreted the document according to what they wished it to mean, rather than according to the intent of Tromp and the majority of the Council Fathers. Thus, when the Vatican clarified in Dominus Iesus (2000) that the Church’s doctrine regarding her exclusive status had not changed, many falsely accused Pope John Paul II of betraying the Council. By then, the erroneous interpretation of Lumen Gentium (and Unitatis Redintegratio) had become so widespread that even well-intentioned Catholics sincerely believed that the Council taught the Church of Christ extended outside the Catholic Church, albeit in an imperfect form. While answering some objections to Dominus Iesus in an interview, Cardinal Ratzinger, who was then prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith and had also attended the Council, he explained the adoption of subsistit rather than est as follows:

The concept expressed by “is” (to be) is far broader than that expressed by “to subsist.” “To subsist” is a very precise way of being, that is, to be as a subject which exists in itself. Thus the Council Fathers meant to say that the being of the Church as such is a broader entity than the Roman Catholic Church, but within the latter it acquires, in an incomparable way, the character of a true and proper subject. (Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, 22 September 2000)

Here the Cardinal understands subsistit to refer to a concrete realization of “Church” as substantial subject. The broader sense of “being” (esse) is well known to those exposed to Scholastic thinking, for it can refer to the order of abstract essences. The “Church of Christ,” considered as a formal essence, is concretely realized in the existent Catholic Church. The Catholic Church is the only existent in which the essence of the Church (“the being of the Church as such”) is realized as “a true and proper subject.” In other words, only of the Catholic Church is it correct to say, “This is the Church of Christ.” This does not exclude, however, the possibility of other groups having attributes that pertain to the essence of the Church of Christ.

After Cardinal Ratzinger became Pope Benedict XVI, he ordered the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith to issue a definitive formal clarification on the meaning of the Vatican Council’s ecclesiology. This explanation is consistent with that given by Cardinal Ratzinger in 2000.

Christ “established here on earth” only one Church and instituted it as a “visible and spiritual community”, that from its beginning and throughout the centuries has always existed and will always exist, and in which alone are found all the elements that Christ himself instituted. “This one Church of Christ, which we confess in the Creed as one, holy, catholic and apostolic […]. This Church, constituted and organised in this world as a society, subsists in the Catholic Church, governed by the successor of Peter and the Bishops in communion with him”.

In number 8 of the Dogmatic Constitution Lumen gentium ‘subsistence’ means this perduring, historical continuity and the permanence of all the elements instituted by Christ in the Catholic Church, in which the Church of Christ is concretely found on this earth.

It is possible, according to Catholic doctrine, to affirm correctly that the Church of Christ is present and operative in the churches and ecclesial Communities not yet fully in communion with the Catholic Church, on account of the elements of sanctification and truth that are present in them. Nevertheless, the word “subsists” can only be attributed to the Catholic Church alone precisely because it refers to the mark of unity that we profess in the symbols of the faith (I believe... in the “one” Church); and this “one” Church subsists in the Catholic Church. (“Responses to Some Questions Regarding Certain Aspects of the Doctrine on the Church,” William Cardinal Levada, 29 June 2007)

Here the Vatican clarifies that “subsistence” contains the sense of perduring or remaining, and that the Catholic Church is the concrete realization of the Church of Christ. It is the only such realization, as is evident from the Creed saying the Church is “one.” Other churches may contain some, but not all, of the elements that define “Church of Christ,” and as such they cannot be properly said to “be” the Church of Christ, though the Church of Christ is in some sense present or operative in them. This is consistent with Fr. Tromp’s understanding, since he objected to adest (“is present”) as being non-exclusive, for the Church of Christ is present in other communities, but this is not the same as saying that it subsists in these communities as a proper subject. As an analogy, the Holy Spirit may be present in a Protestant congregation, but this does not make it proper to say the congregation is the Holy Spirit or a part of the Holy Spirit. Similarly, the presence of the Church of Christ in such a congregation does not mean that the congregation is the Church or part of the Church. It could hardly be otherwise, since Protestants have a fundamentally different understanding of ecclesiology.

The ecclesiological teaching from Rome has been consistent, from Pius XII through the Second Vatican Council, Pope Paul VI, Pope John Paul II, and Pope Benedict XVI. For anyone to resist this teaching because it does not jibe with one’s preferences is to lose the essence of Catholicism, aptly expressed by St. Augustine: Ubi Petrus, ibi ecclesia. Laymen, priests, bishops and theologians may lapse into error from time to time, but Rome remains to help regain one’s bearings. Whoever rejects this guidance, preferring his own counsel instead, will find himself moving further and further from the faith, and toward increasing antagonism with a Church in which he has only nominal membership.

Having at last clarified that the Catholic Church remains the sole concrete realization of the Church of Christ, we can now turn to the other aspect of Lumen Gentium’s ecclesiology, declaring that “many elements of sanctification and of truth are found outside [the Catholic Church’s] visible structure.” (LG, 8) Here ‘elements’ should not be understood to mean the “marks of the Church,” for there are only four of those, not “many”: one, holy, catholic and apostolic. ‘Elements of sanctification’ is an informal term for the various supernatural goods that the Catholic Church has long acknowledged to exist among non-Catholic Christians. Notably, the Church has long recognized the validity of most Protestant baptisms. This is not a small thing, considering the tremendous sanctifying power the Church ascribes to baptism. Baptism is the means by which Christ incorporates a believer into His Body, which is the Church. By acknowledging Protestant baptisms, the Catholic Church has admitted that Protestants are in some sense members of the Church. This is not by virtue of being in a Protestant congregation as such, but by virtue of the sacrament that has been entrusted to the Church. Indeed, all elements of sanctification are “gifts belonging to the Church of Christ,” the Council teaches.

Since the various elements of sanctification found among non-Catholic Christians are “gifts belonging to the Church of Christ,” which is concretely manifested in the Catholic Church alone, these elements are “forces impelling toward catholic unity.” In other words, the Scripture, the sacraments, and the various sanctifying graces have all been entrusted to the Church of Christ, which concretely is the Catholic Church. Thus, when other Christians receive these elements of sanctification, they are receiving what is proper to the one Church of Christ, not to their various groups. As such, these sanctifying elements tend to incline the recipient toward the one Church which is their proper source. If this were not the case, the Holy Spirit would be opposed or indifferent to the Church’s unity, which is emphatically not the case, as Scripture attests. Stated simply, the more sanctifying elements a Christian community shares with the Catholic Church, the more apt such a community is for eventual reunion with the Church, the source of all sanctifying elements. Such reunion will enable the visibly separated Christians to fully participate in the unity that the Catholic Church already enjoys.

Although the Church has such an exalted origin and status, she must nonetheless conduct her mission in a spirit of humility and service, following her Founder. She has special concern for the poor and afflicted, and serves Christ by relieving their need. Like Christ, she embraces sinners, so she is “at the same time holy and always in need of purification,” and follows the path of penance and renewal. By the power of Christ, the Church may overcome its challenges, and “reveal to the world, faithfully though darkly, the mystery of its Lord until, in the end, it will be manifested in full light.” (LG, 8)

It is commonly said that the Second Vatican Council redefined the Church as “the people of God,” as if to impose some new democratic emphasis on the Church’s constitution. In fact, the Council’s definition of the Church was already given in the first chapter as the Mystical Body of Christ. In this second chapter, the term ‘people of God’ is used as practically synonymous or co-extensive with the Church. Its primary purpose is to emphasize the collective nature of the Church: “God, however, does not make men holy and save them merely as individuals, without bond or link between one another. Rather has it pleased Him to bring men together as one people…” (LG, 9)

The concept of “people of God” also enables the Church to articulate a continuity with the Old Testament and with non-Christians. Israel, of course, was the first people to be chosen by God, to be educated and made holy through His covenant. “All these things, however, were done by way of preparation and as a figure of that new and perfect covenant, which was to be ratified in Christ…” The new covenant, foretold by the prophets, where the law of God is inscribed on men’s hearts, was instituted in Christ’s Blood, “calling together a people made up of Jew and gentile, making them one, not according to the flesh but in the Spirit. This was to be the new People of God.” (LG, 9)

This redeemed people, made holy by Christ’s sacrifice, has Christ for its head. “The state of this people is that of the dignity and freedom of the sons of God… Its end is the kingdom of God, which has been begun by God Himself on earth, and which is to be further extended until it is brought to perfection by Him at the end of time…” Although this messianic people “does not actually include all men,” it is “a lasting and sure seed of unity, hope and salvation for the whole human race.” This people is used by God “as an instrument for the redemption of all, and is sent forth into the whole world as the light of the world and the salt of the earth.” (LG, 9) Here the Council appeals to the perennial Christian belief that all creation will be renewed at the end of time, and the whole human race in this new creation will consist of the saved. This does not mean that even the damned will then be saved, as various universalists have held. Although redemption is offered to all, some may freely choose not to accept this invitation.

“Israel according to the flesh, which wandered as an exile in the desert, was already called the Church of God. So likewise the new Israel… is called the Church of Christ.” (LG, 9) The Council does not fear to call the Church of Christ “the new Israel.” This Israel is united not merely according to the flesh, but also in the Spirit, so it is not limited by race. “God gathered together as one all those who in faith look upon Jesus as the author of salvation and the source of unity and peace, and established them as the Church that for each and all it may be the visible sacrament of this saving unity.” (cf. St. Cyprian, Ep. 69, 6) Christ is the source of the Church’s unity, and we join the Church through faith in Christ.

Since all Christians are united in Christ the high priest, we are “a kingdom and priests to God the Father.” (Rev 5:10) The Council says all Christians “should present themselves as a living sacrifice, holy and pleasing to God.” More precisely, according to Romans 12:1, we should present our reasonable (i.e., spiritual) service as a living sacrifice to our bodies. (When the verse is correctly translated, “reasonable service” is the direct object and “bodies” is the indirect object.) This service is an acceptable and pleasing sacrifice to God not by our own virtue, but in virtue of the perfect sacrifice of Christ. All of our priestly and sacrificial activity is but a participation in the priestly and sacrificial action of Christ. This participation obligates all Christians to “bear witness to Christ and give an answer to those who seek an account of that hope of eternal life which is in them.” (LG, 10)

The Council recognizes a distinction between “the common priesthood of the faithful” and “the ministerial or hierarchical priesthood” as two different ways of participating in “the one priesthood of Christ.” (cf. Pope Pius XII) The ordained priest has a special power to teach and rule “the priestly people.” He acts in persona Christi to make the Eucharist present, “and offers it to God in the name of all the people.” Yet the faithful also join in the offering of the Eucharist by virtue of their “royal priesthood” (1 Peter 2:9), as Pope Pius XI explained at length in Miserentissimus Redemptor (n.9). “They likewise exercise that priesthood in receiving the sacraments, in prayer and thanksgiving, in the witness of a holy life, and by self-denial and active charity.” (LG, 10)

The priestly life of the faithful is exercised through the sacraments. The baptized “must confess before men the faith which they have received.” They are “more perfectly bound to the Church” in Confirmation, which endows them with spiritual strength “so that they are more strictly obliged to spread and defend the faith”. The apex of Christian life is offering the Eucharistic sacrifice, where the faithful offer the Divine Victim and themselves along with It, though not in the same way as the ministerial priest (who alone acts in persona Christi). Through the Sacrifice and through Holy Communion, the faithful concretely manifest the unity of the people of God realized through the Sacrament. Reconciliation with the Church is achieved through Penance, and the anointing of the sick associates the afflicted with the passion and death of Christ. Those in Holy Orders feed the Church “with the word and the grace of God.”

Lastly, Christians living in matrimony have their own special gift, as St. Augustine teaches. They help each other to attain holiness and raise their children in the faith. In the family, new members of society are born, perpetuating the Church across the ages. “The family is, so to speak, the domestic church. In it parents should, by their word and example, be the first preachers of the faith to their children…” (LG, 10)

The people of God also participate in Christ’s prophetic office, spreading a living witness to Him. “The entire body of the faithful, anointed as they are by the Holy One, cannot err in matters of belief.” (LG, 12) This sensus fidelium is infallible only when “they show universal agreement in matters of faith and morals.” [Emphasis added.] Such discernment “is exercised under the guidance of the sacred teaching authority, in faithful and respectful obedience to which the people of God accepts that which is… truly the word of God.” Naturally, there can be no universal consensus that does not include the bishops, so the sensus fidelium fidei is not some sort of democratic counterweight to hierarchical authority. Nor is it a basis for inventing new doctrine as popular opinions change, for “the people of God adheres unwaveringly to the faith given once and for all to the saints, penetrates it more deeply with right thinking, and applies it more fully in its life.”

While diverse charisms or spiritual gifts may be distributed throughout the Church, “judgment as to their genuinity and proper use belongs to those who are appointed leaders in the Church.” (LG, 12)

“All men are called to belong to the new people of God.” (LG, 13) This one people has members from all nations, and since Christ’s kingdom is not of this world, joining the people of God “takes nothing away from the temporal welfare of any people.” All that is good in their customs is preserved and ennobled.

Particular Churches within the Church “retain their own traditions, without in any way opposing the primacy of the Chair of Peter, which presides over the whole assembly of charity and protects legitimate differences, while at the same time assuring that such differences do not hinder unity but rather contribute toward it.” (LG, 13) The particular Churches, like individuals within the Church, have different gifts, and each member supplies what the rest of the body may lack. In this way, even diversity contributes to unity, as is seen in the distinctions of rank and status within the Church.

This Sacred Council wishes to turn its attention firstly to the Catholic faithful. Basing itself upon Sacred Scripture and Tradition, it teaches that the Church, now sojourning on earth as an exile, is necessary for salvation. Christ, present to us in His Body, which is the Church, is the one Mediator and the unique way of salvation. In explicit terms He Himself affirmed the necessity of faith and baptism and thereby affirmed also the necessity of the Church, for through baptism as through a door men enter the Church. Whosoever, therefore, knowing that the Catholic Church was made necessary by Christ, would refuse to enter or to remain in it, could not be saved. (LG, 14)

The Catholic Church, that is, the visible Church “sojourning on earth,” is necessary for salvation. This is because Christ is the sole mediator and way of salvation, and He is present to us in His Body, the Church. Baptism is the means of entering the Church, so to refuse baptism is to refuse entry. Anyone aware of Christ’s affirmation of the necessity of faith and baptism for salvation is obligated to enter and remain in the Church in order to be saved.

Those who are united to the visible bodily structure of the Church, ruled by Christ through the Pope and bishops, are “fully incorporated in the society of the Church.” Men are visibly bonded to the Church through “profession of faith, the sacraments, and ecclesiastical government and communion.” Yet the one who “does not persevere in charity” is not saved, even though he is part of the body of the Church, yet not “in his heart.” Bodily membership in the Church is no guarantee of salvation. “All the Church's children should remember that their exalted status is to be attributed not to their own merits but to the special grace of Christ. If they fail moreover to respond to that grace in thought, word and deed, not only shall they not be saved but they will be the more severely judged.” (LG, 14)

“Catechumens who, moved by the Holy Spirit, seek with explicit intention to be incorporated into the Church are by that very intention joined with her. With love and solicitude Mother Church already embraces them as her own.” (LG, 14) This is the so-called “baptism of desire,” which is sufficient for salvation if death should intervene before the catechumen can be baptized with water. It is not mere human volition, but the Holy Spirit moving the catechumen to faith, that saves.

“The Church recognizes that in many ways she is linked with those who, being baptized, are honored with the name of Christian, though they do not profess the faith in its entirety or do not preserve unity of communion with the successor of Peter.” (LG, 15) Here we find the Council’s first “ecumenical” gesture, acknowledging a bond with non-Catholic Christians. The Catholic Church had always implicitly acknowledged such a bond, by recognizing the validity of non-Catholic baptism. In the apostolic letter Praeclara gratulationis (1894), Pope Leo XIII acknowledged that even those who do not profess the entire Catholic faith bear the name of Christians. Yet Pope Leo added that “they could never be united to Jesus Christ, as their Head if they were not members of His Body, which is the Church; nor really acquire the True Christian Faith if they rejected the Legitimate teaching confided to Peter and his Successors.” While the Council confirms that those outside the Church lack the unity which depends on communion with Christ’s Vicar, at the same time it says they are “united with Christ” through baptism. That is to say, they retain the indelible character imparted by baptism, which as St. Thomas Aquinas teaches, is a “participation in Christ’s priesthood, flowing from Christ himself.” (Summa Theol., III, 63, 3)

The Council describes other Christians as belonging to “Churches or ecclesiastical communities.” (LG, 15) This roughly corresponds to the Orthodox and the Protestants, respectively. Though lacking full communion with the universal Church, the Eastern Orthodox had long been tacitly recognized by the Catholic Church as Particular Churches, by acknowledging the validity of their episcopacy and their Eucharist, which constitute the basis of unity in a Particular Church. In Rerum Orientalium (1928), Pope Pius XI spoke of the Orthodox as “those brethren and sons of Ours, so long separated from Us.” Pope Pius XII, in Orientalis Ecclesiae (1944), called the Orthodox “our separated brethren and children,” and invoked the blessing of St. Cyril: “Behold the sundered members of the Body of the Church are reunited once again, and no further discord remains to divide the ministers of the Gospel of Christ.” Clearly, the Churches of the East retain some degree of communion with the Catholic Church, by participating in a valid Eucharist, yet their status as Particular Churches is “wounded” by their lack of communion with the Holy See, which “is not an external complement to the particular Church, but one of its internal constituents,” as Cardinal Ratzinger explained in a 1992 letter to all Catholic bishops.

The Council acknowledges that supernatural gifts are given even to non-Catholic Christians: “Likewise we can say that in some real way they are joined with us in the Holy Spirit, for to them too He gives His gifts and graces whereby He is operative among them with His sanctifying power. Some indeed He has strengthened to the extent of the shedding of their blood.” (LG, 15) These graces are not something external to the Catholic Church, for as was said earlier, all such “elements of sanctification” are “gifts belonging to the Church of Christ.” (LG, 8) Such graces are found among non-Catholic Christians only to the extent that they still retain some degree of communion with the Catholic Church, through baptism, the Eucharist, or the profession of faith.

Since it is the same Holy Spirit that gives grace to all Christians, this Spirit impels them toward unity, in accordance with Christ’s will:

In all of Christ’s disciples the Spirit arouses the desire to be peacefully united, in the manner determined by Christ, as one flock under one shepherd, and He prompts them to pursue this end. Mother Church never ceases to pray, hope and work that this may come about. She exhorts her children to purification and renewal so that the sign of Christ may shine more brightly over the face of the earth. (LG, 15)

The Council is not saying there is anything deficient in the unity of the visible Catholic Church. On the contrary, it was earlier stated that the visible Catholic Church is the Church of the Creed, which is “one, holy, catholic and apostolic.” (LG, 8) Rather, those who are in imperfect communion with the Catholic Church, by virtue of the same sanctifying Holy Spirit, are impelled to seek that perfect union which is willed by Christ. (John 17:21) The Council’s teaching makes plain the error of setting up ecumenism in opposition to a call to conversion. Christians outside of visible Catholic unity are sanctified not by their local virtues, but by the Holy Spirit that unifies the Body of Christ as a living Body. To the extent that there are authentic elements of sanctification outside the visible structure of the Catholic Church, those elements will direct men toward Catholic unity. If it were otherwise, Christ would be impossibly opposed to Himself.

This ecclesiology can make sense only if we appreciate that Christians are saved not merely as individuals, but as “one people” (LG, 9) in a corporate unity, the Body of Christ. It is through this union that men are saved. Vatican II’s discussion of “the people of God” cannot be understood in the sense of classical liberal democracy, consisting of autonomous individuals entering a compact to guarantee their private rights. In contrast with Lockean individualism, the Church is strongly communitarian: “if one member endures anything, all the members co-endure it, and if one member is honored, all the members together rejoice.” (LG, 7) This is in strict continuity with the attitude of ancient Israel, where the sins of one affected the entire community, and all were responsible for the welfare of widows and the poor. This solidarity is in marked contrast with the “mind your own business” individualism of libertarian democracy.

The “people of God,” we recall, consists of all those who live as the Body of Christ with Christ as their Head. Yet as St. Thomas Aquinas taught, Christ is potentially the Head of all living men, since his power suffices for the salvation of every living human, provided their consent by free will. Therefore, as long they live on this earth, every unbaptized man is potentially in the Church. (Summa Theol., III, 8, 3) With reason, then, the Council declares that “those who have not yet received the Gospel are related in various ways to the people of God.” (LG, 16)

“On account of their fathers [the Jewish] people remains most dear to God, for God does not repent of the gifts He makes nor of the calls He issues.” (LG, 16) Here the Council gives its first clear statement of the positive value of the Jewish people. While it may seem obvious to us now, at the time it was commonly believed that the Jews were cursed by God for having executed Christ, though no such teaching was ever sanctioned by the magisterium. On the contrary, the Catechism of the Council of Trent taught that Christians who sin are more culpable than the Jews for Christ’s suffering.

In this guilt are involved all those who fall frequently into sin; for, as our sins consigned Christ the Lord to the death of the cross, most certainly those who wallow in sin and iniquity crucify to themselves again the Son of God, as far as in them lies, and make a mockery of Him. This guilt seems more enormous in us than in the Jews, since according to the testimony of the same Apostle: If they had known it, they would never have crucified the Lord of glory; while we, on the contrary, professing to know Him, yet denying Him by our actions, seem in some sort to lay violent hands on him. (Roman Catechism [1566], The Creed, Article 4)

The Council takes the next logical step, and recognizes that the present-day Jews cannot be accursed for that for which they are not chiefly culpable. Yet it goes further, and says they are actually “dear to God,” not on account of their unbelief, but “on account of their fathers.” As surely as God loves Abraham and the other patriarchs, He will surely honor His promise to bless their carnal descendants. God’s preference for the Jews was expressed by Christ: “I was not sent but to the sheep that are lost of the house of Israel.” (Matt. 15:24) “And when he drew near, seeing the city, he wept over it.” (Luke 19:41)

But the plan of salvation also includes those who acknowledge the Creator. In the first place amongst these there are the Mohammedans, who, professing to hold the faith of Abraham, along with us adore the one and merciful God, who on the last day will judge mankind. Nor is God far distant from those who in shadows and images seek the unknown God, for it is He who gives to all men life and breath and all things, and as Saviour wills that all men be saved. (LG, 16)

Since God’s “plan of salvation” is implemented solely through the Church, the Council is here asserting that the Church is linked in some way to all who believe in the Creator. This is most obviously the case with the Muslims, who share our belief in the one God of Abraham. It cannot be said that the God of Islam is another false god, even if the Muslims might differ from Christians in theological doctrines. They clearly give honor to the Creator, not a mere creature, and respect His sovereignty over all men. This ability to recognize the one God is a gift of the Holy Spirit administered through the Church. Going further, St. Paul famously commended the Athenians for honoring a mere “unknown God.” (Acts 17:23) Though they had no positive understanding of the one God as the Muslims do, they at least had the inclination to honor that which transcended their understanding of creation. This seeking is also a gift of the Holy Ghost to the Church. We should not be surprised to see this salvific activity beyond the visible structure of the Church, given the Savior’s desire for all men to be saved. (1 Tim. 2:4)

Those also can attain to salvation who through no fault of their own do not know the Gospel of Christ or His Church, yet sincerely seek God and moved by grace strive by their deeds to do His will as it is known to them through the dictates of conscience. Nor does Divine Providence deny the helps necessary for salvation to those who, without blame on their part, have not yet arrived at an explicit knowledge of God and with His grace strive to live a good life. Whatever good or truth is found amongst them is looked upon by the Church as a preparation for the Gospel. She knows that it is given by Him who enlightens all men so that they may finally have life. (LG, 16)

The possibility of salvation for the inculpably ignorant is not a new teaching, but was already articulated a century earlier by Bl. Pope Pius IX in Quanto Conficiamur (1863):

There are, of course, those who are struggling with invincible ignorance about our most holy religion. Sincerely observing the natural law and its precepts inscribed by God on all hearts and ready to obey God, they live honest lives and are able to attain eternal life by the efficacious virtue of divine light and grace. Because God knows, searches and clearly understands the minds, hearts, thoughts, and nature of all, his supreme kindness and clemency do not permit anyone at all who is not guilty of deliberate sin to suffer eternal punishments. (Quanto Conficiamur, 7)

This acknowledgement of the salvation of those not visibly connected to the Church does not contradict the ancient doctrine extra ecclesia nulla salus, for these divine gifts are administered through the Church. Pope Pius, in fact reaffirms the traditional doctrine in the words that follow:

Also well known is the Catholic teaching that no one can be saved outside the Catholic Church. Eternal salvation cannot be obtained by those who oppose the authority and statements of the same Church and are stubbornly separated from the unity of the Church and also from the successor of Peter, the Roman Pontiff… (Quanto Conficiamur, 8)

The hope of salvation for the “invincibly ignorant” is no cause for relief among those who consciously and virulently oppose the Catholic Church. Salvation outside her visible structure, being the work of the same Spirit that unifies the Church, can only impel non-Christians to view the Church more favorably. Whoever hates the Catholic Church does not have the Holy Spirit, and opposes Christ. “He who hears you hears me, and he who rejects you, rejects me, and he who rejects me, rejects him who sent me.” (Luke 10:16) “He who does not believe will be condemned.” (Mark 16:16) Unbelief is culpable only when the Gospel has been clearly presented and consciously rejected. There can be no opposition among the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, so there can be no salvific action where there is opposition to the Son and His Body the Church.

The Church nonetheless has an urgent mission, because of the real danger of the loss of salvation among those outside her visible structure:

But often men, deceived by the Evil One, have become vain in their reasonings and have exchanged the truth of God for a lie, serving the creature rather than the Creator. Or some there are who, living and dying in this world without God, are exposed to final despair. Wherefore to promote the glory of God and procure the salvation of all of these, and mindful of the command of the Lord, “Preach the Gospel to every creature,” the Church fosters the missions with care and attention. (LG, 16)

There is no salvation for those who put their trust in perishable things, as do those who devote their life to the pursuit of wealth and worldly pleasure. This foolish idolatry is shared even by those intellectuals who effectively ascribe divine power to natural objects, conceiving them as having no need of a Creator. The prevalence of this belief is due to vanity, not intelligence, for the philosophically sophisticated will recognize the radical contingency of the natural order, even when this order is expressed in mathematical terms. In these materialist cultural tendencies, we see an aversion to salvific action, as misguided people seek a false self-sufficiency that can only end in death, as they would cut themselves off from the Source of life. Others separate themselves from God not because they have misplaced trust in mere creatures, but because they despair altogether. In all these cases, the Church is doing an inestimable service by preaching the Gospel, offering wisdom to vain fools and hope to the disconsolate.

The modern Church has not abandoned her imperative to preach the Gospel to all nations: “For the Church is compelled by the Holy Spirit to do her part that God’s plan may be fully realized, whereby He has constituted Christ as the source of salvation for the whole world.” (LG, 17) As the Church brings the Gospel to those in “the slavery of error and of idols,” she purifies and perfects “whatever good lies latent in the religious practices and cultures of diverse peoples.” The obligation to evangelize binds all the faithful, though “the priest alone can complete the building up of the Body in the eucharistic sacrifice.” Committed to evangelizing all nations, “the Church both prays and labors in order that the entire world may become the People of God.” This sense of universal mission has no hint of religious indifferentism, and is consistent with the Church’s perennial conviction that the Gospel is the perfection and fulfillment of all that is good in the hopes of the nations.

The Council’s continuity with tradition is reiterated as Lumen Gentium affirms the hierarchical constitution of the Church.

This Sacred Council, following closely in the footsteps of the First Vatican Council, with that Council teaches and declares that Jesus Christ, the eternal Shepherd, established His holy Church, having sent forth the apostles as He Himself had been sent by the Father; and He willed that their successors, namely the bishops, should be shepherds in His Church even to the consummation of the world. And in order that the episcopate itself might be one and undivided, He placed Blessed Peter over the other apostles, and instituted in him a permanent and visible source and foundation of unity of faith and communion. And all this teaching about the institution, the perpetuity, the meaning and reason for the sacred primacy of the Roman Pontiff and of his infallible magisterium, this Sacred Council again proposes to be firmly believed by all the faithful. (LG, 18)

Here the Council unequivocally states its intent to retain the First Vatican Council’s teaching about apostolic succession and the primacy of the Pope, as traditionally interpreted, and this teaching is de fide. There is no basis for the claim that Vatican II altered the basic monarchical constitution of the Church.

By the will of the Lord Jesus, the Church was “established on the apostles and built upon blessed Peter, their chief, Christ Jesus Himself being the supreme cornerstone.” (LG, 19) The apostle were organized as a college with Peter as their head, with the mission that they “might make all peoples His disciples, and sanctify and govern them.” They passed on to their successors “the duty of confirming and finishing the work begun by themselves.” In particular, those appointed to the episcopate received the apostolic office in an unbroken succession, as St. Irenaeus (2nd cent.) testified.

Bishops, assisted by priests and deacons, preside in place of God over the flock, acting “as teachers for doctrine, priests for sacred worship, and ministers for governing.” (LG, 20) Just as the special office of Peter is passed on to his successors, so does the “apostles’ office of nurturing the Church” permanently persist among the bishops. The bishops are shepherds appointed by Christ, and he who hears them, hears Christ, while he who rejects them, rejects Christ. (Lk. 10:16) The apostolic teaching authority of all bishops had long been acknowledged by the Popes (e.g., Leo XIII in Et sane), and is not construed in a way that derogates from the Church’s monarchical constitution. The college of the apostles, the Council said earlier, was ordered with Peter at the head, and so a bishop can only truly act in his apostolic office if he is union with Peter’s successor, or else we would have to say that Christ opposes Christ.

The Council teaches that in episcopal consecration the fullness of the sacrament of Orders is conferred. Priests and deacons, who are ordained to assist bishops, lack the fullness of the apostolic office, though they perform various ministerial functions. Thus only bishops can admit other members to the episcopate. Incidentally, by specifying that only bishops have the fullness of Orders, while the others have a limited ministry, the Council renders practically irrelevant the historical disputes as to whether the various specific ministries were clearly distinguished in the first century, or what the terms episkopoi and presbyteroi signified in the New Testament. All that matters is that only some received the fullness of apostolic authority, while others were restricted to an auxiliary role.

The collegiate nature of the episcopate is evidenced by the various councils held from the earliest ages, in order to ensure that the various particular Churches acted in accord. “But the college or body of bishops has no authority unless it is understood together with the Roman Pontiff, the successor of Peter as its head. The pope’s power of primacy over all, both pastors and faithful, remains whole and intact.” (LG, 22) The Pope is “Vicar of Christ and pastor of the whole Church,” having “full, supreme and universal power over the Church.” He can exercise his power freely, while the bishops can exercise their universal power only with the consent of the Roman Pontiff, when assembled in an ecumenical council. “A council is never ecumenical unless it is confirmed or at least accepted as such by the successor of Peter; and it is prerogative of the Roman Pontiff to convoke these councils, to preside over them and to confirm them.” (LG, 22) Again, there is no hint of any anti-monarchical or conciliarist tendency in Lumen Gentium.

Just as the Pope is the visible source of unity among the world’s bishops and all the faithful, so is each bishop the source of unity in his particular church. Apart from the exercise of local authority, each bishop is called “to be solicitous for the whole Church, and this solicitude, though it is not exercised by an act of jurisdiction, contributes greatly to the advantage of the universal Church.” (LG, 23) In the Patristic era, we find numerous examples of bishops who sought to safeguard unity of faith and discipline among the various particular churches, though they claimed no jurisdiction outside their diocese.

Although the Council is not altering the Church’s constitution, it is reminding the bishops of their ancient duty to participate in affairs beyond the diocesan level. They “are obliged to enter into a community of work among themselves and with the successor of Peter.” (LG, 23) After the Council, the bishops would take a much more active role in universal Church affairs, either through national conferences or special commissions headed by the Vatican. These may be seen as successors to the regional synods and other episcopal collaborations that were frequent in the first millennium.

The Council also alludes to the Eastern Churches (“the ancient patriarchal churches”) as a model of collegiality, noting that a shared liturgical and spiritual heritage causes closeness among bishops in each rite. This unity in a common interest is a model for collegiality in other parts of the Church.

A principal mission of bishops is to proclaim the Gospel, and they accordingly have a divine teaching authority. “In matters of faith and morals, the bishops speak in the name of Christ and the faithful are to accept their teaching and adhere to it with a religious assent.” (LG, 25) A special submission must be shown “to the authentic magisterium of the Roman Pontiff, even when he is not speaking ex cathedra.” Reverence and adherence to papal teaching is not limited to formal, infallible definitions, but applies to all judgments made “according to his manifest mind and will.” The Pope’s “mind and will in the matter may be known either from the character of the documents, from his frequent repetition of the same doctrine, or from his manner of speaking.”

It is already evident that the post-conciliar spirit of dissent among “liberal” Catholics has no basis whatsoever in the Second Vatican Council. The Council unambiguously reaffirmed the supremacy of the papal magisterium over that of the bishops, and commanded religious obedience to every papal judgment on faith and morals. Any Catholic who pretends to have the Council’s blessing in opposing the teaching of the Pope (or one’s bishop) is either profoundly ignorant of what the Council teaches, or completely uninterested in the truth. The intellectually honest will recognize that the spirit of dissent is not found in Vatican II. Instead, it may be found in Martin Luther’s doctrine of private interpretation, or in John Locke’s principle of individual sovereignty, or in Friedrich Nietzsche’s enshrinement of the will as its own arbiter of right action—in a word, in any one of the numerous modern ideologies that would make each man his own pope, subject to few, if any, higher criteria. To be opposed to authority as such (rather than just the abuse of authority) is an attitude more in line with Milton’s proud Lucifer than with the humble Son of Man who was obedient unto death.

Catholics had long recognized that some teachings not only command religious obedience, but are properly infallible and irreformable, due to Christ’s promise that he would never allow His Church as a whole to fall into error. Earlier in this document, it was mentioned that a matter of faith is infallibly true if it is held as such by the entire body of the faithful. The First Vatican Council formally defined that papal teaching is infallible when the Pope is acting in his role as universal pastor. Papal infallibility was not defined until the nineteenth century, because only then did the Pope’s supreme magisterium face serious internal challenge. Yet the infallibility of the ecumenical councils was never formally defined, though it is no less certainly part of Catholic tradition. The present document briefly addresses this topic.

Although the individual bishops do not enjoy the prerogative of infallibility, they nevertheless proclaim Christ’s doctrine infallibly whenever, even though dispersed through the world, but still maintaining the bond of communion among themselves and with the successor of Peter, and authentically teaching matters of faith and morals, they are in agreement on one position as definitively to be held. This is even more clearly verified when, gathered together in an ecumenical council, they are teachers and judges of faith and morals for the universal Church, whose definitions must be adhered to with the submission of faith. (LG, 25)

The indefectibility of the Church entails that it is impossible for all the bishops to be in error on a matter of faith. When all the bishops in communion with the Pope agree that a certain position on faith or morals is to be held definitively, this judgment is infallible and de fide. It is not necessary for them to be physically convened in a single location to exercise this infallibility, though the mechanism of an ecumenical council obviously facilitates the clear and definite expression of the will of all the bishops at once. The authority of ecumenical councils, then, derives from the grace of infallibility that the bishops have as a corporate whole, though not as individuals, just as the body of the faithful are infallible as a corporate whole, not as individuals. This collectivist notion of infallibility re-emphasizes the essentially corporal nature of the Church, as contrasted with the individualism of those who would make private judgment the measure of faith and morality. Infallibility, like indefectibility in general, derives from unity in Christ, not from individual human members.

The doctrine of papal infallibility does not contradict the principle just articulated, for the Pope makes ex cathedra pronouncements not as a private individual, but as the visible source of unity in the Church. Communion with the Pope is the standard for inclusion in the college of bishops with the grace of infallibility, and it is also the standard for inclusion in the body of the faithful who cannot err when they are in universal agreement on Christian faith or morals. The Pope, then, as the source of unity, cannot fail to give authentic teaching when acting as Pope:

And this is the infallibility which the Roman Pontiff, the head of the college of bishops, enjoys in virtue of his office, when, as the supreme shepherd and teacher of all the faithful, who confirms his brethren in their faith, by a definitive act he proclaims a doctrine of faith or morals. And therefore his definitions, of themselves, and not from the consent of the Church, are justly styled irreformable, since they are pronounced with the assistance of the Holy Spirit, promised to him in blessed Peter, and therefore they need no approval of others, nor do they allow an appeal to any other judgment. For then the Roman Pontiff is not pronouncing judgment as a private person, but as the supreme teacher of the universal Church, in whom the charism of infallibility of the Church itself is individually present… (LG, 25)

It is doubtful that even the most resourceful Catholic dissident can find here any diminution of the notion of papal infallibility pronounced at the First Vatican Council. Whoever denies the infallibility of the Pope’s definitive teaching opposes Vatican II.

We see in the higher tiers of infallibility a safeguard for when there are divisions of opinion within the Church. If the faithful are divided in opinion, then the common agreement of the bishops, as expressed in ecumenical councils for example, suffices as a sure guide for authentic Catholic teaching. If the bishops are divided, as has happened on many occasions in history, then a definition by the Pope will “confirm his brethren,” the bishops, and settle their dispute. Non-Catholics often erroneously suppose that Catholic teaching on controversial matters is to be settled by opinion polls of the laity, but the faithful represent authentic Catholic teaching only when they are in practically unanimous agreement, not when they are divided. Controversy is to be settled by each bishop in his diocese, and if there are disputes among bishops, we do not take a poll of the bishops, but refer matters to the Pope. A divided college of bishops cannot guarantee authentic teaching, which is why no document of an ecumenical council is approved by a simple majority, but near unanimity is required. Doctrinal controversy in the Church is not resolved by simple majoritarianism, as in democracy, but by more direct application to the visible source of unity, the Pope.

The Pope and the bishops, when pronouncing judgments, are bound by “Revelation which as written or orally handed down is transmitted in its entirety through the legitimate succession of bishops and especially in care of the Roman Pontiff himself.” (LG, 25) These teachers of the Church “strive to inquire properly into that revelation and to give apt expression to its contents; but a new public revelation they do not accept as pertaining to the divine deposit of faith.” That is, definitions expound the deposit of faith given to the apostles, but do not add any new revelation.

“This Church of Christ is truly present in all legitimate local congregations” (LG, 26) by virtue of celebration of the Eucharist, through which all are assimilated to Christ and united in Him. “Every legitimate celebration of the Eucharist is regulated by the bishop,” so there can be no Church of Christ without a governing bishop, though local congregations under pastors are rightly called churches.

A bishop governs his particular church with a power that “is proper, ordinary and immediate, although its exercise is ultimately regulated by the supreme authority of the Church, and can be circumscribed by certain limits, for the advantage of the Church or of the faithful.” (LG, 27) That is, the bishop’s power is not derived from the Pope, but nonetheless the Pope may circumscribe that power for the good of the universal Church. Bishops can make laws and pass judgments in their dioceses. “The pastoral office or the habitual and daily care of their sheep is entrusted to them completely; nor are they to be regarded as vicars of the Roman Pontiffs, for they exercise an authority that is proper to them, and are quite correctly called ‘prelates,’ heads of the people whom they govern.” The bishop governs not to be served, but to serve, caring for the faithful as his sons. He should therefore listen to them and cooperate with them. He must care even for “those who are not yet of the one flock,” that is, non-Catholic Christians or catechumens in his diocese. He is responsible for the souls of all those entrusted to him. The faithful, for their part, “must cling to their bishop, as the Church does to Christ.”

The bishops, sent into the world like their predecessors the apostles, may grant degrees of participation in their ministry to others to assist them. First among these are priests, who “although they do not possess the highest degree of the priesthood, and although they are dependent on the bishops in the exercise of their power, nevertheless they are united with the bishops in sacerdotal dignity,” since they can offer the Sacrifice of the Eucharist. They are also consecrated to preach the Gospel and shepherd the faithful. They are true priests, partaking in Christ’s function as sole Mediator. (LG, 28)

Priests cooperate with their bishops, whom they assist, and “constitute one priesthood with their bishop although bound by a diversity of duties.” In a sense, they make their bishop present in their local communities. Priests should reverently obey their bishop as a father, while the bishop should regard priests as co-workers, sons and friends.

All priests are bound together in a common brotherhood by virtue of their ordination, and they each have the duty to minister to all the baptized in their care, even those who have left the faith. They must set a good Christian example in their lives, and they should combine, under the leadership of the bishops and the Pope, to “wipe out every kind of separateness, so that the whole human race may be brought into the unity of the family of God.” (LG, 28)

Deacons are ordained “not unto the priesthood, but unto a ministry of service.” (LG, 29) They serve the bishop and his priests. His duties are “to administer baptism solemnly, to be custodian and dispenser of the Eucharist, to assist at and bless marriages in the name of the Church, to bring Viaticum to the dying, to read the Sacred Scripture to the faithful, to instruct and exhort the people, to preside over the worship and prayer of the faithful, to administer sacramentals, to officiate at funeral and burial services.” (LG, 29) These are all traditional functions of the order of deacon, but in practice the diaconate was a preparatory stage for the priesthood. There did not seem to be a need for deacons who were not priests, as had been the case in the early Church.

Now, however, the Council saw that the duties enumerated “can be fulfilled only with difficulty in many regions in accordance with the discipline of the Latin Church as it exists today.” (LG, 29) There was a shortage of priests to perform such tasks, owing to the stringent disciplinary criteria for the Latin priesthood, most especially the requirement of celibacy. A permanent diaconate (as opposed to the “transitional” diaconate of the seminaries) could provide needed assistance in such areas, but only if they were dispensed from some of the disciplinary criteria required of priests. Thus the Council proposes that “the diaconate can in the future be restored as a proper and permanent rank of the hierarchy,” and that this order can, with the Pope’s consent, “be conferred upon men of more mature age, even upon those living in the married state.” The territorial conferences of bishops may determine whether and where it is opportune to establish permanent deacons. The permanent diaconate “may also be conferred upon suitable young men, for whom the law of celibacy must remain intact.”

Pope Paul VI established the permanent diaconate in 1967, and various territorial conferences petitioned Rome thereafter to establish diaconates in their territories. It is often said that the Pope “restored” the diaconate, following the language of the Council quoted above. While it is true that having a diaconate that is permanent rather than temporary is a restoration of early Church practice, the modern permanent diaconate differs significantly from its ancient predecessor. Ancient deacons were bound by all the disciplines required of clerics, including continence (cf. St. Epiphanius Haer., lix, 4), wearing clerical garb, and abstaining from various secular activities forbidden to clerics. Also, the ancient deacons did not perform baptisms or other sacraments except in grave necessity; ordinarily, they only assisted the priests at these ceremonies, having care of the sacred vessels. Some of these limitations are reflected in the practice of the Eastern Orthodox, who still have permanent deacons to assist the priests with the liturgy. Orthodox deacons are not even allowed to give sacramental blessings. The modern Latin diaconate, then, should be understood as a new discipline reflecting distinctively modern needs.

In practice, the new permanent diaconate consists almost exclusively of married men, though the Council and Pope Paul also made provision for celibate young men. The higher age requirement for married deacons (thirty-five rather than twenty-five) is explained in the 1983 Code of Canon Law as allowing time for the candidate to have proven stability and responsibility in his family life. Although canon law still requires continence of all clerics (1983 CIC 277), this is not strictly demanded of married deacons. A 1998 directive issued by the Congregation for the Clergy calls for a “chastity which flourishes, even in the exercise of paternal responsibilities, by respect for spouses and the practice of a certain continence.” (Directory for the Ministry and Life of Permanent Deacons, 61)

The Council now turns its attention specifically to the laity, namely those members of the People of God who belong neither to the clergy nor to the religious orders. The laity in their own way participate in the prophetic, priestly, and kingly roles of Christ.

“What specifically characterizes the laity is their secular nature.” (LG, 31) Since they are engaged in secular activities, their vocation is to “seek the kingdom of God by engaging in temporal affairs and by ordering them according to the plan of God.” In this way, they help sanctify the world even in its secular operations. Thus the laity are not just Christians who happen to be in the world, but they are positively called to bring Christianity into their worldly activities. We can see how the secularist notion of separating religious and temporal affairs is fundamentally incompatible with the Christian religion. Christianity, the religion of the Incarnate God, would have us “work for the sanctification of the world from within as a leaven.”

The Church is composed of many members, who do not all have the same function, yet they all work for a common goal, and are united in “one Lord, one faith, one baptism.” (LG, 32) Since we all have the same calling to perfection and one salvation, there is “in Christ and in the Church no inequality on the basis of race or nationality, social condition or sex.” (cf. Gal. 3:28) Although different members may proceed along different paths, and “by the will of Christ some are made teachers, pastors and dispensers of mysteries on behalf of others, yet all share a true equality with regard to the dignity and to the activity common to all the faithful for the building up of the Body of Christ.”

The distinction of those in ordained ministry from the laity is not a cause of division but of unity, since both work to a common goal and have mutual need of each other. The clergy have teaching authority in order to serve the good of the laity. They are superiors by virtue of their duty, but they are brothers of the laity as Christians, just as Christ is both Lord and brother of the elect. The Council cites St. Augustine: “For you I am a bishop; but with you I am a Christian. The former is a duty; the latter a grace.”

The laity are commissioned to participate in the Church’s salvific mission by virtue of baptism and confirmation. Their station in life enables them to carry the Gospel to areas that would otherwise be inaccessible. Besides this general commission to spread the Gospel, “the laity can also be called in various ways to a more direct form of cooperation in the apostolate of the Hierarchy.” (LG, 32) A similar exhortation was made by Pope Pius XII:

It is clear that the ordinary layman can resolve and it is highly desirable that he should so resolve — to cooperate in a more organized way with ecclesiastical authorities and to help them more effectively in their apostolic labor. He will thereby make himself more dependent on the Hierarchy, which is alone responsible before God for the government of the Church. (Guiding Principles of the Lay Apostolate, 1957)

A more active laity is not conceived as rivalling the hierarchy, but rather as being more dependent on the latter’s teaching and government. Pope Pius found it foolish to speak of a vain power struggle between clergy and laity, for “the tasks before the Church today are too vast to leave room for petty disputes.” Instead, he reminds Catholics: “Respect for the priestly dignity has always been one of the most characteristic traits of the Christian community; on the other hand, laymen also have rights, and the priest must recognize them.”

The Second Vatican Council seems to go slightly further than Pope Pius, declaring that the laity “have the capacity to assume from the Hierarchy certain ecclesiastical functions, which are to be performed for a spiritual purpose.” (LG, 33) These functions would be identified later by the Council as including “the teaching of Christian doctrine, certain liturgical actions, and the care of souls. By virtue of this mission, the laity are fully subject to higher ecclesiastical control in the performance of this work.” (Apostolicam Actuositatem [1965], 24)